They Don’t Want You to Read

What Dostoevsky Can Still Teach Us About Being Human

There are books that feel like they were never meant for everyone. You don’t find them advertised. You don’t stumble across them on a trending list. They sit quietly on shelves, waiting for someone with enough curiosity or restlessness to open them.

When you do, you know right away that you’re holding something different. The words seem alive. They speak with an intensity that modern writing rarely reaches. They don’t flatter you or entertain you. They disturb you. They whisper things you half-suspected were true but didn’t have the courage to say out loud.

That’s the moment you realize how rare real thought has become.

We live in a time when people think information is the same as knowledge. We scroll endlessly through opinions, all of them shallow variations of the same few ideas. Everyone seems to be saying something, but almost no one is thinking. And when someone does think… really think… it almost feels out of place, even offensive.

Books like Dostoevsky’s are dangerous because they remind you that thinking isn’t comfortable. Real thought doesn’t make you feel good. It unsettles you. It breaks the neat structure of what you think you believe. It exposes your contradictions, your motives, your fears. And once you’ve gone through that process, you can’t go back to the soft comfort of ignorance.

That’s why they don’t want you to read this book.

When I say “they,” I don’t mean a group of people sitting around deciding what you can and can’t read. I mean the invisible machinery of comfort… the entire ecosystem built on keeping you docile, distracted, and endlessly entertained. It’s not a conspiracy. It’s a culture that rewards conformity.

The modern world runs on comfort. Everything is designed to make you feel safe, validated, and constantly stimulated. The news keeps you angry, the algorithms keep you busy, and the entertainment keeps you numb. You can live an entire life inside that loop and never once stop to ask what any of it means.

But a book like The Brothers Karamazov or Crime and Punishment breaks that spell.

It’s not that Dostoevsky wants to shock you. He’s not a provocateur. What he does is worse. He tells the truth about what’s inside people… the pride, the guilt, the jealousy, the yearning for meaning that never quite goes away. He makes you see that beneath the polite exterior of civilization, there’s still chaos and desire and a hunger for God. And the moment you see that, the surface of modern life starts to look paper-thin.

That’s why people avoid reading him. Because he doesn’t let you escape yourself.

Don’t forget to join our FREE book club!

We started a digital book club to study the great texts of Western Civilization — from Dante to Dostoevsky — together. Inside, you’ll get:

Live community book discussions (bi-weekly)

New, deep-dive literature essays every week

The entire archive of book reviews + our 100 great texts reading list

Our first discussion on Confessions by Saint Augustine is on October 28th at 12pm ET. Bring your thoughts, questions, and favorite passages!

Sign up below to attend — all paid members can join the live discussion up on stage…

Note: paid subscribers via Substack will automatically receive an access link for the live calls.

The Age of Distraction

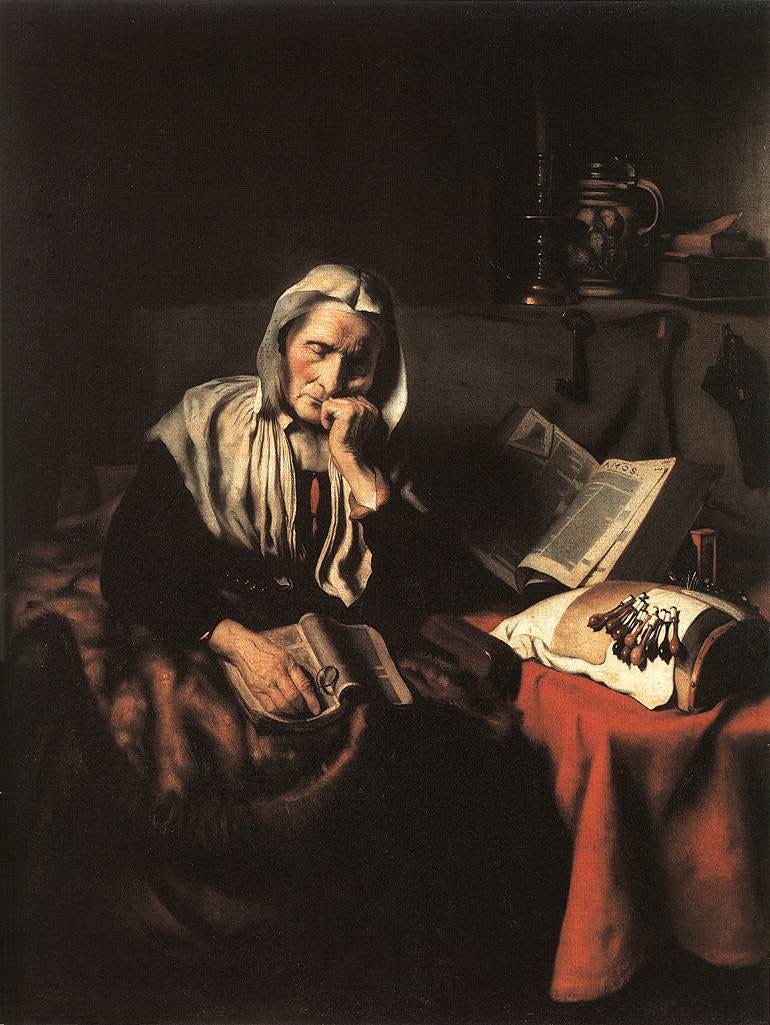

Most people today can’t read Dostoevsky, not because they’re stupid, but because they’ve forgotten how to sit with discomfort.

To read him, you have to slow down. You have to give your attention to something that doesn’t reward you right away. The sentences are long. The ideas take time to build. There are no bullet points, no dopamine hits, no quick conclusions. You have to struggle with it. And that struggle is what modern life tries hardest to eliminate.

Every innovation of the last fifty years has been about removing friction. Everything is made to be instant. You don’t wait, you don’t work for it, you don’t earn it… you tap, and it appears. We call that progress, but what it’s really done is train people out of patience.

But books like Dostoevsky’s require patience. They’re not puzzles you solve; they’re experiences you endure. You don’t come out of them the same.

When you read Notes from Underground, for example, you meet a man so brutally honest about his own pettiness and weakness that it’s almost unbearable. He hates himself, yet he’s proud of that hatred. He admits to sabotaging his own happiness out of spite. You read it and realize you’ve done the same things, only you never said them out loud.

That’s the genius of Dostoevsky. He takes everything we hide… everything polite society teaches us to bury… and brings it right to the surface. He exposes the ugly parts of the human soul, not to glorify them, but to show that without grace, without something higher to live for, we collapse into madness.

The modern world avoids that truth. It wants you to think that all problems can be solved by comfort and consumption. If you’re anxious, there’s a product. If you’re lonely, there’s an app. If you’re lost, there’s a new ideology. Anything but silence and reflection.

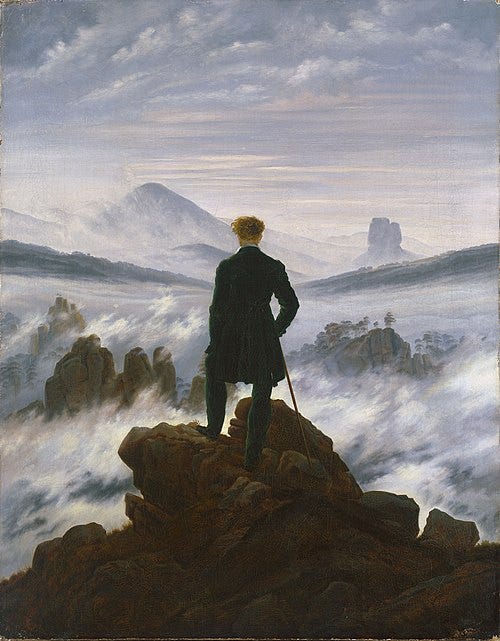

But the books they don’t want you to read are the ones that teach you to face silence again. To sit with guilt. To suffer meaningfully. To think in solitude. That’s where real change happens.

Crime and Punishment: The War Within

If you want to understand why Dostoevsky matters, start with Crime and Punishment.

On the surface, it’s a murder story. A poor student named Raskolnikov kills an old pawnbroker. But that’s not what the book is about. The real story begins after the murder, in the endless, tormenting dialogue inside Raskolnikov’s mind.

He kills because he believes he’s above morality. He wants to test whether he’s extraordinary… whether he has the right to overstep conventional laws for the sake of a higher good. It’s the modern idea of utilitarianism taken to its extreme: if the act produces a greater benefit, then it’s justified.

But Dostoevsky shows how false that logic is. Raskolnikov’s crime doesn’t liberate him. It destroys him. The guilt eats at him until he’s trapped in a psychological hell. The brilliance of the novel is that his punishment doesn’t come from the police… it comes from his own conscience.

Dostoevsky understood something that modern psychology still struggles to explain: moral guilt isn’t a social construct. It’s spiritual. When we break the moral order of the world, something inside us breaks too. We can deny it for a while, but the truth always comes back.

In the end, Raskolnikov only finds peace through confession and suffering. The book ends not with triumph, but with redemption. Through pain, he becomes human again.

That’s the lesson the modern world hates most: that suffering can be sacred.

Everything today is built around avoiding pain. But Dostoevsky insists that without it, we remain shallow. Suffering burns away illusions. It humbles us. It makes us see what we are. That’s why Crime and Punishment still feels more relevant than any self-help book ever written. It doesn’t offer comfort; it offers truth.

The Brothers Karamazov: The Question of God

If Crime and Punishment is about guilt, The Brothers Karamazov is about faith. It’s the most profound exploration of belief ever put into fiction.

The story revolves around three brothers, each representing a different response to life’s deepest question: is there meaning, or is everything chaos?

Dmitri is passion… raw, impulsive, ruled by emotion. Ivan is intellect… the modern skeptic, too smart to believe. Alyosha is faith… the one who still sees holiness in a broken world.

The novel’s center is Ivan’s rebellion against God. He doesn’t deny that God exists; he simply refuses to accept Him. He looks at the suffering of children and says, if that’s the price of paradise, I return my ticket. It’s one of the most powerful moments in literature because it’s not cynical… it’s sincere. Ivan’s argument is brilliant, emotional, and devastating.

But Dostoevsky’s answer doesn’t come through debate. It comes through love. Alyosha doesn’t refute his brother; he lives differently. He forgives, he listens, he suffers with people. Dostoevsky shows that faith isn’t an argument… it’s an orientation of the heart.

In that sense, The Brothers Karamazov is more than a novel. It’s a confrontation with modern nihilism. It predicts what would happen to a world that kills God. The chaos, the alienation, the emptiness… it’s all there, written a century before Nietzsche or Freud.

When people say Dostoevsky was prophetic, this is what they mean. He saw that once belief collapses, nothing can fill its place. Politics tries. Psychology tries. Ideology tries. But none of them can satisfy the soul’s hunger for meaning.

That’s why the book feels so relevant now. We live in Ivan’s world. A world of endless information and no wisdom. A world where people talk about morality without believing in anything higher than themselves. Dostoevsky saw where that would lead: to despair.

But he also saw the cure. Love grounded in faith. Compassion rooted in truth. The kind of goodness that doesn’t need applause.

That’s the message they don’t want you to hear… because it points beyond everything the modern world sells.

Notes from Underground: The Birth of Modern Man

If there’s one book that explains the modern psyche better than any psychology textbook, it’s Notes from Underground.

It’s written as the confession of a man who has withdrawn completely from society. He’s bitter, proud, and self-aware to the point of paralysis. He mocks everything and everyone, including himself. He knows exactly how miserable he is, but refuses to change.

That’s the underground man. He’s the prototype of the modern intellectual… too intelligent to believe in anything, too cowardly to live sincerely. He overthinks everything until he destroys every possibility of happiness.

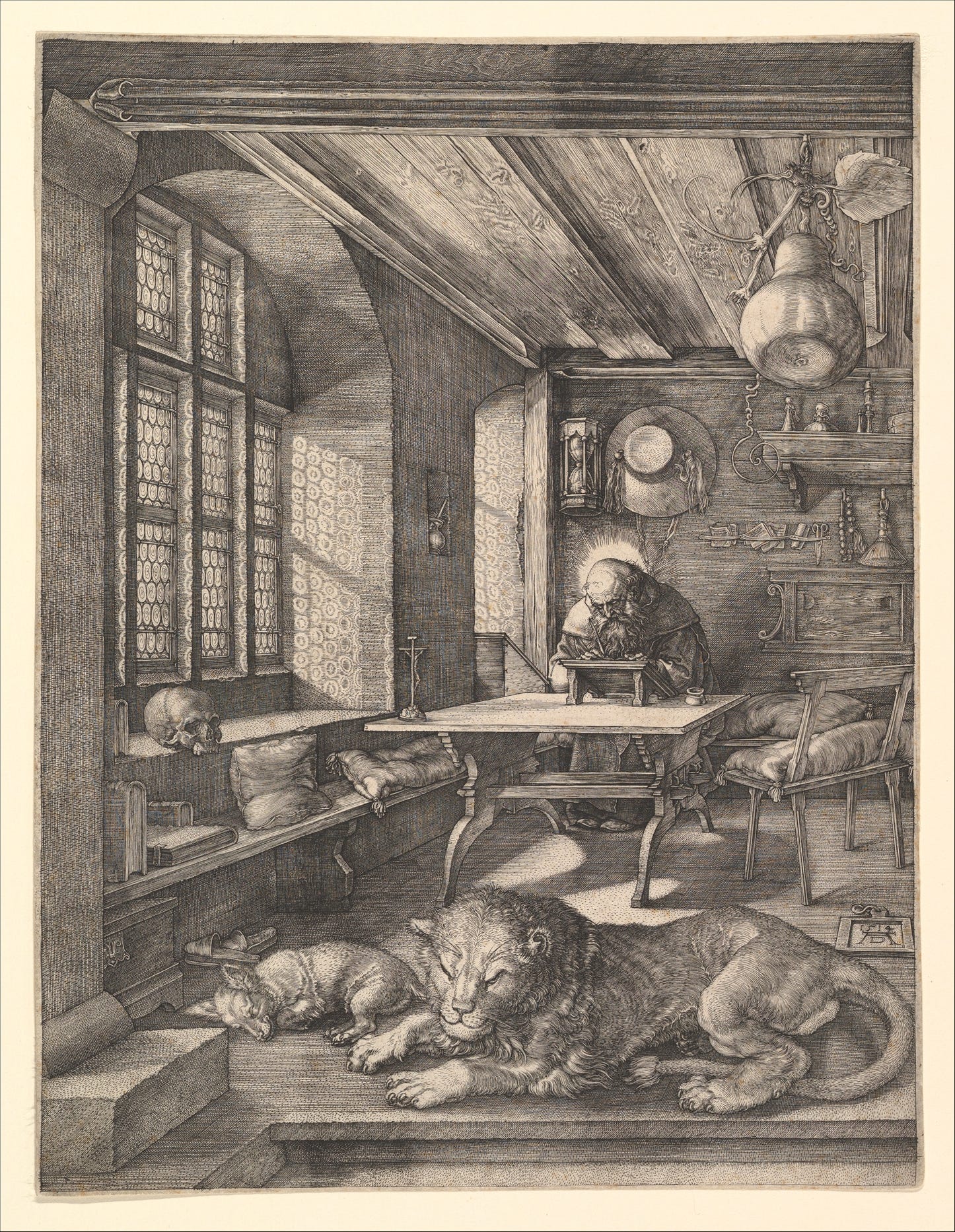

What Dostoevsky does in that short novel is astonishing. He shows how rationalism and ego, when taken to their logical conclusion, lead to self-destruction. The underground man wants total freedom, but that freedom makes him miserable. Without faith or purpose, freedom becomes chaos.

When people talk about “existentialism,” they usually start with Sartre or Camus. But Dostoevsky got there first, and he went deeper. He didn’t just describe the problem… he showed its consequences. A man who denies transcendence eventually denies himself.

The underground man is modern man. He’s the person who hides behind irony, who mocks everything sacred because he’s afraid of being sincere. He’s the person who replaces morality with cleverness. He’s the one who confuses cynicism for intelligence.

Reading Notes from Underground feels like holding a mirror to the 21st century. We’re surrounded by underground men now… people who can explain everything, justify everything, and yet believe in nothing.

That’s what makes Dostoevsky dangerous. He sees through irony. He calls it what it is: fear.

The Possessed: Ideology and Madness

Before the twentieth century unleashed its totalitarian ideologies, Dostoevsky predicted them. In The Possessed (also known as Demons), he shows how a society that loses its faith becomes vulnerable to madness disguised as progress.

The novel is about a group of radicals who want to overthrow everything… religion, morality, tradition. They believe that if they destroy the old world, a perfect one will rise from the ashes.

Sound familiar?

Dostoevsky shows how this revolutionary dream turns into nightmare. The characters believe they’re liberating humanity, but what they create is chaos and death. Once they reject God, there’s nothing left to guide them but ego and resentment.

The result is demonic.

When you read The Possessed today, you realize how accurately Dostoevsky foresaw the 20th century: the gulags, the purges, the re-education camps, the utopias that turned into prisons. He understood that once people stop believing in God, they don’t stop believing… they just start believing in something worse.

That’s why modern institutions prefer you to stay at the surface. They’ll happily teach you about history or economics, but they’ll never encourage you to read The Possessed. Because once you do, you’ll see through their illusions. You’ll understand how easily ideology becomes idolatry.

What They Really Fear

When you read Dostoevsky deeply, you stop being easy to manipulate. You develop what the world fears most: an inner life.

An inner life means you can be alone without being lonely. It means you can think without needing constant validation. It means your values come from conviction, not from whatever trend happens to dominate the moment.

That’s what “they” don’t want. They want people who react, not people who reflect. Because reflection slows everything down. It breaks the cycle of impulse. It reminds you that there’s something more important than attention or approval.

When you have an inner life, you can’t be fully controlled. That’s why people like Dostoevsky matter more than ever. His books train your soul to resist manipulation. They teach you how to think morally, not just intellectually.

Why Reading Him Still Matters

Every generation thinks it’s different. We assume that technology changes the essence of life. But it doesn’t. The core of being human hasn’t changed since Dostoevsky’s time. We still want to be loved. We still struggle with guilt. We still long for meaning.

The danger now is that we’re losing the language to talk about those things. We speak in slogans, in politics, in metrics. But the deeper vocabulary… the one that deals with sin, grace, redemption… is disappearing.

Dostoevsky keeps that language alive. He reminds us that the soul is real. That you can’t measure everything. That not all suffering is meaningless.

The Real Reason They Don’t Want You to Read

They don’t want you to read this book because once you do, you’ll start asking questions that don’t have simple answers.

You’ll wonder why so much of life feels empty. Why comfort doesn’t satisfy. Why people who seem to have everything are still restless. You’ll start seeing that the real problem isn’t outside… it’s inside.

And when you start looking inward, you stop being predictable. You stop consuming so much. You stop chasing the same illusions. You begin to live differently.

That’s what books like Dostoevsky’s do. They don’t just inform you… they transform you. They make you dangerous, in the best possible way.

Because a person who can think deeply, who can suffer meaningfully, who can stand alone and still believe in truth… that person can’t be controlled.

And that’s why they don’t want you to read this book.

Great piece. Will dust down my Dostoevsky again.

One typo: he was not 'a century' before Nietzsche but just a few years. 'The Brothers K' was 1880 and 'Beyond good and Evil' was 1886.

Terrific essay. Thank you.