The Search for Truth

What does it mean to seek truth — and finally find rest?

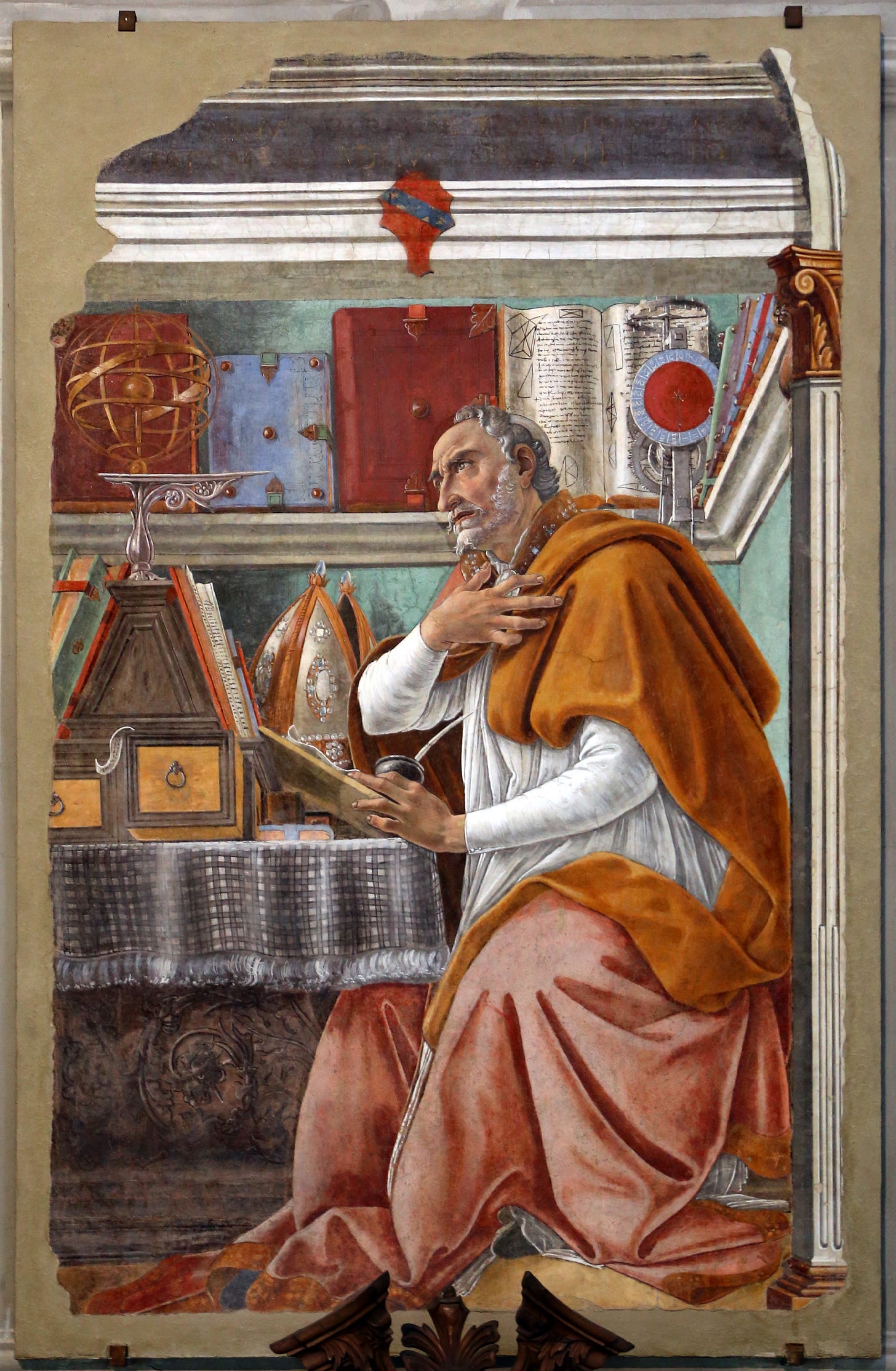

Every age thinks it’s the first to feel lost. But more than sixteen hundred years ago, one man described that feeling so completely that it still sounds modern. His name was Augustine. He lived in a crumbling empire, surrounded by wealth, distraction, and confusion. He had every chance to succeed… he was intelligent, ambitious, and popular… yet something in him refused to rest.

He searched for meaning in love, philosophy, and success, but each new discovery left him emptier than before. When he finally found peace, he wrote it down.

The result was Confessions, the first real autobiography in history, and still one of the most honest books ever written.

Don’t forget to join our FREE book club!

We started a digital book club to study the great texts of Western Civilization — from Dante to Dostoevsky — together. Inside, you’ll get:

Live community book discussions (bi-weekly)

New, deep-dive literature essays every week

The entire archive of book reviews + our 100 great texts reading list

Our first discussion on Confessions by Saint Augustine is on October 28th at 12pm ET. Bring your thoughts, questions, and favorite passages!

Sign up below to attend — all paid members can join the live discussion up on stage…

Note: paid subscribers via Substack will automatically receive an access link for the live calls.

The Man Behind the Book

Augustine was born in 354 AD in North Africa, in what is now Algeria. His father was a pagan official; his mother, Monica, was a devout Christian. From the beginning, he lived between two worlds… one of faith, one of ambition. He studied rhetoric, the art of persuasion, and became a brilliant speaker. His mind was sharp, but his desires were stronger. In his youth he lived a life of pleasure and pride. He took a mistress, had a son, and joined a religious sect called the Manichees, who claimed to explain the world through reason and dualism… light versus darkness, spirit versus matter.

Augustine wanted truth, but he also wanted admiration. That conflict drives the early chapters of Confessions. He writes about his boyhood with a mixture of amusement and shame. He remembers stealing pears from a neighbor’s tree, not because he wanted them, but because it was forbidden. That story might sound small, but it becomes the seed of his lifelong question: why do we do what we know is wrong? The theft of the pears is the first moment Augustine sees sin for what it is… not hunger for fruit, but hunger for rebellion.

The Form of Confession

The title Confessions has several meanings. It’s not just an admission of guilt. In Latin, confessio means both confession and praise. Augustine’s book is both… a confession of failure and a confession of faith. He writes not to boast or entertain but to tell the truth before God. The whole book is addressed directly to Him. Each line begins and ends in prayer. “You have made us for Yourself,” Augustine says, “and our hearts are restless until they rest in You.” That sentence became the key to Western spiritual life. It explains what drives him and, by extension, all of us.

Confessions is not arranged like a normal memoir. It moves between memory and meditation, between events and thoughts. Augustine doesn’t just recount what happened; he examines why it mattered. He sees his past as a map of divine patience. Every mistake, every delay, becomes proof of a grace that never gave up on him. That’s why the book still feels alive. It’s not about ancient philosophy. It’s about the interior life… the world within the world, the place where a person meets themselves.

The Search for Truth

In his twenties, Augustine left Africa and went to Rome, then to Milan, to teach rhetoric. He was successful, but empty. He kept searching for truth that satisfied both mind and heart. The Manichees promised logical explanations, but their system fell apart when he began to ask hard questions. He turned next to Neoplatonism, the philosophy of Plato revived by thinkers like Plotinus. That philosophy taught him that truth exists beyond the material world, that the soul is higher than the senses. It brought him closer to God but stopped short of grace.

He writes about this period with affection and frustration. He found beauty in ideas but no power to live them. His intellect could reach upward, but his will stayed chained to habit. “I was bound,” he says, “not with an iron chain, but with the obstinacy of my own will.” That line captures the mystery of sin that Augustine discovered: it’s not just doing wrong; it’s being unable to stop wanting it.

When he heard Bishop Ambrose preach in Milan, something changed. Ambrose was not emotional or manipulative. He was rational and calm. Augustine admired him at first for his eloquence, then for his peace. Slowly, the barrier between reason and faith began to dissolve. Augustine realized that faith was not the enemy of intellect but its fulfillment.

The Conversion

The climax of Confessions comes in Book VIII, the story of his conversion. It’s one of the most famous scenes in literature. Augustine is in a garden, tormented by indecision. He knows what he should do… give up his old life… but he can’t. He describes it as being torn between two wills, one new and one old. He throws himself under a fig tree and weeps. In that moment, he hears a child’s voice from a nearby house singing, tolle lege — “take up and read.”

He takes it as a command, picks up the Bible, and opens it at random. His eyes fall on Romans 13: “Not in rioting and drunkenness, not in chambering and wantonness, but put on the Lord Jesus Christ, and make no provision for the flesh.” He reads no further. “In an instant,” he writes, “it was as though the light of confidence flooded my heart, and all the darkness of doubt vanished away.”

It’s a quiet moment, but it changes everything. Augustine becomes a Christian, gives up his career, and prepares for baptism. His mother, Monica, who had prayed for him for decades, lives long enough to see his conversion. Their conversation before her death is one of the most tender passages in the book… two souls resting together after a lifetime of searching.

The Nature of Memory

In the later books of Confessions, Augustine turns inward. He begins to analyze memory, time, and creation with the same care he once used on rhetoric. These sections are some of the most profound reflections ever written. He asks how memory works… how we can remember joy and grief, colors and words, things and feelings. He concludes that memory is not just a storehouse but a mystery… a vast landscape where the self lives.

When Augustine examines time, he notices that the present is always slipping away. The past is memory, the future is expectation, and the present is a vanishing point. Yet somehow we live in all three at once. He realizes that only God, who is outside of time, can hold it together. This realization connects philosophy and prayer: to think clearly about time is to feel the need for eternity.

These chapters can seem abstract, but they’re really about dependence. Augustine sees that even thought itself depends on grace. The mind can search, but it cannot find truth without being guided. For him, reason and revelation are not enemies but parts of one movement… the soul turning toward its source.

Sin and Grace

One of the reasons Confessions endures is its honesty about sin. Augustine doesn’t romanticize it. He calls it what it is: disorder. Sin is loving lower things more than higher ones, loving the gift more than the giver. He writes about how easily the heart attaches itself to pleasure, success, or pride… not because they are evil, but because they are finite. When we demand from them what only God can give, they collapse.

Grace, in his view, is not a reward but a rescue. It’s God bending down to heal the will from within. Augustine describes his conversion not as a decision he made but as a surrender that happened to him. “You called,” he says, “and broke through my deafness. You shone, and your light drove away my blindness.” That is the language of someone who has discovered that strength does not come from trying harder but from finally giving up control.

The balance between human freedom and divine grace became the center of Augustine’s later theology. He insisted that people can choose, but their choosing is itself touched by grace. Without that, the will is a prisoner of its own desires. His insight shaped the next thousand years of Christian thought, from Aquinas to Luther.

The Mother and the Son

Monica, Augustine’s mother, appears throughout Confessions like a quiet thread. She prays, weeps, and waits. Her patience becomes one of the book’s hidden miracles. For years she follows her son across continents, never losing hope. When Augustine finally turns to faith, she rejoices not as someone vindicated but as someone set free.

Their final meeting in Ostia, as they look out over the sea, is one of the most moving passages in any Christian text. They talk about heaven and feel for a moment that they have touched it. “We rose,” Augustine writes, “even beyond our own souls, to that region of never-failing plenty, where you feed Israel forever with the food of truth.” Shortly after, Monica dies. Augustine’s grief is quiet, without bitterness. Her faith has done its work.

This relationship grounds the book’s philosophy in love. It shows that the search for God is never only intellectual. It begins in longing… in the love between mother and child, between the human and the divine.