The Most Practical New Year’s Resolutions Ever Written

Why Most New Year’s Resolutions Fail

Every year, millions of people sit down and decide to become better versions of themselves. They promise to read more, work harder, eat cleaner, think positively, or finally do the thing they’ve been postponing. These resolutions feel serious in January and faintly ridiculous by March.

The usual explanation is weak willpower. But that explanation doesn’t hold up. People summon willpower all the time for difficult things… jobs, children, emergencies. The real problem is that most resolutions are not designed to survive contact with daily life. They are vague, emotional, and detached from systems.

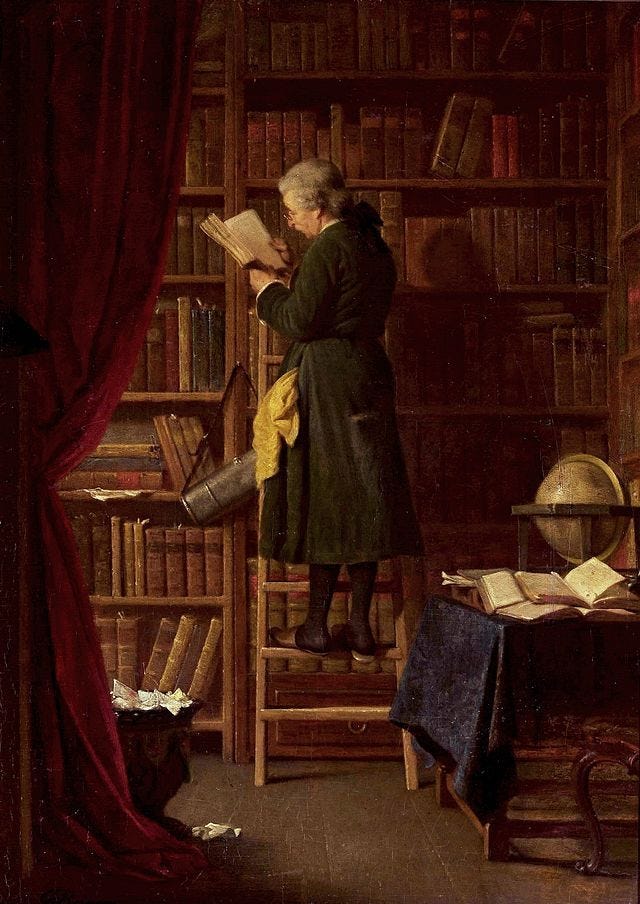

Benjamin Franklin understood this centuries ago. Long before productivity apps, habit trackers, or self-help books, Franklin built one of the most rigorous self-improvement systems in history. What’s remarkable is not that he wanted to be virtuous, but that he treated virtue like a practical skill that could be trained.

Franklin’s resolutions were not about feeling inspired. They were about building a structure that made improvement inevitable. His method still works because human nature hasn’t changed. We are distracted, inconsistent, proud, and forgetful. Franklin was all of those things too.

This essay is about what Franklin actually did, why it worked, and what his approach reveals about how people really change..

Thank you for being part of our mission! If you’d like to support us, and join in the book club sessions directly, please consider a paid subscription. You’ll get:

All live book discussions and recordings (biweekly)

Regular essays to guide you through the books we’re reading

The full archive of articles, essays, and podcasts

Access to our community of readers

Our first discussion on The Everlasting Man by G. K. Chesterton takes place on January 6 at 12pm ET — join us!

Note: all paid members can join the live discussions up on stage. You’ll receive Zoom links shortly before each session.

An Unremarkable Young Man

Franklin is often remembered as a finished product: the wise elder, the statesman, the inventor, the printer of maxims. But he did not start that way. As a young man, he was impulsive, argumentative, vain, and indulgent. He liked to win debates more than to find truth. He wasted time. He chased pleasure.

What makes Franklin unusual is not that he had flaws, but that he wrote them down.

Most people avoid looking directly at their weaknesses. Franklin studied his. He believed that moral failure was not mysterious. It was mechanical. If you could observe it clearly, you could redesign your behavior around it.

This mindset mattered. Franklin did not think of himself as a sinner needing redemption or a genius destined for greatness. He thought of himself as a project. That framing removed drama and added leverage.

Instead of asking whether he was a good person, he asked how to become more useful, more reliable, and more disciplined over time.

That shift… from identity to process… is the foundation of everything that followed.

Turning Morality into Instructions

Franklin’s most famous self-improvement tool was his list of thirteen virtues. What’s striking about the list is not the virtues themselves, which are fairly traditional, but how Franklin defined them.

Each virtue came with a short, precise rule. Temperance was not “moderation in all things.” It was “eat not to dullness; drink not to elevation.” Silence was not “be thoughtful.” It was “speak not but what may benefit others or yourself.”

These definitions matter because they are testable. At the end of the day, Franklin could ask himself whether he had eaten to dullness or spoken without benefit. There was no hiding behind good intentions.

Most modern resolutions fail because they cannot be checked. You cannot measure whether you “focused more” or “lived authentically.” Franklin removed ambiguity. He forced clarity.

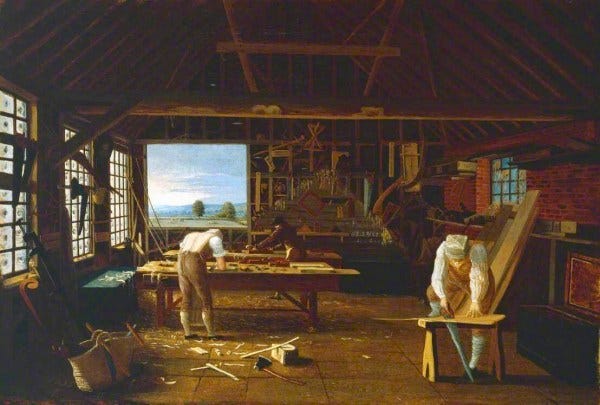

Another important detail is that Franklin’s virtues were not heroic. They were mundane. Order. Industry. Frugality. Sincerity. These are not traits that make for exciting stories, but they are the traits that compound.

Franklin understood that greatness is usually built from boring behaviors repeated consistently. He did not chase moral grandeur. He chased reliability.

The Power of Sequential Focus

Franklin made another decision that seems obvious in hindsight but is still rarely followed: he worked on only one virtue at a time.

Rather than trying to become a perfect person all at once, he devoted a week to each virtue. During that week, his primary goal was not to be flawless, but to notice violations. When the week ended, he moved on to the next virtue, cycling through all thirteen repeatedly over the year.

This approach solved a common problem. When people try to improve everything at once, they improve nothing. Attention is limited. Franklin treated attention as a scarce resource and allocated it deliberately.

There is also something psychologically powerful about narrowing the scope. Focusing on one virtue makes failure informative rather than discouraging. If you fail at everything, you feel hopeless. If you fail at one specific thing, you learn something concrete.

Franklin did not expect perfection. He expected progress through iteration.

This is closer to how engineers build systems than how moralists preach virtue. Franklin was closer to an engineer than a preacher.

Making Failure Visible

Franklin tracked his behavior in a small notebook. Each page had columns for the days of the week and rows for the virtues. When he violated a rule, he marked it.

This seems simple, but it does something profound. It externalizes conscience. Instead of relying on memory or mood, Franklin created a physical record of his actions.

Most people underestimate how forgiving memory can be. We forget failures quickly and remember intentions generously. Franklin removed that bias by writing things down.

The notebook also changed the emotional tone of failure. A mark on a page is less dramatic than a moral judgment. It turns failure into data. Data invites adjustment, not shame.

Franklin noticed patterns. Certain virtues were harder for him than others. Order, in particular, resisted his efforts. He admitted that despite trying, he never fully mastered it. This honesty is important. Franklin’s system was not about pretending to be better than he was. It was about seeing reality clearly.

Progress does not require self-deception. It requires accurate feedback.

Ambition Without Self-Deception

Franklin was extremely ambitious. He wanted influence, respect, and accomplishment. But his resolutions were private. He did not broadcast them. He did not seek applause for working on himself.

This separation matters. When improvement becomes performative, it loses effectiveness. You start optimizing for how progress looks rather than how it works.

Franklin optimized for results. His notebook was for him alone. There was no social reward for honesty, which made honesty more likely.

This is one reason his system still feels modern. Many contemporary self-improvement efforts are tangled with identity signaling. Franklin avoided that trap by keeping the work quiet and the standards internal.

He was ambitious, but his ambition was disciplined.

Why Franklin’s Method Still Works

Franklin’s resolutions worked because they aligned with how humans actually behave.

They assumed forgetfulness, so they relied on written reminders.

They assumed inconsistency, so they focused on patterns over time.

They assumed pride, so they reduced self-judgment and emphasized observation.

Most importantly, they assumed that change is incremental.

Franklin did not believe that a new year magically transformed a person. The New Year mattered only because it provided a convenient checkpoint. What mattered was the daily work.

In that sense, Franklin’s resolutions were not really about January. They were about building a life that improved through attention and repetition.

What Franklin Would Think of Modern Resolutions

If Franklin looked at modern New Year’s resolutions, he would probably find them well-intentioned but poorly designed. Too many are emotional. Too few are operational.

“Be healthier” would confuse him. He would ask: healthier how? What actions? How often? What counts as failure?

Franklin would not reject ambition. He would reject vagueness.

He would likely advise fewer resolutions, written more precisely, tracked more honestly, and reviewed more frequently.

And he would remind us of something uncomfortable: most people don’t fail because their goals are too hard, but because they never turned them into systems.

Resolution as Craft, Not Aspiration

Benjamin Franklin treated self-improvement as a craft. Like printing or writing or diplomacy, it required tools, feedback, and patience. He did not wait to feel motivated. He built structures that worked even when motivation faded.

That is why his resolutions endure. They were not expressions of hope. They were plans.

The lesson is not to copy Franklin’s thirteen virtues or his notebook exactly. The lesson is to adopt his mindset. Define improvement precisely. Focus narrowly. Track honestly. Iterate patiently.

A New Year does not change you. What changes you is what you do on ordinary days, when no one is watching, and nothing feels dramatic.

Franklin understood that. And that is why his resolutions still matter.

Please suggest some readings related to his 13 virtues

This is an excellent essay. Thank you for this information.