The Most Disciplined Man in History

A story of discipline, duty, and the search for freedom

There are few names in philosophy as towering as Immanuel Kant. He is often placed beside Plato and Aristotle, because after him, no one could think about knowledge, morality, or freedom in quite the same way. His ideas reshaped modern thought. His writings are among the most difficult in the world, yet behind them lies something surprisingly human: the effort of a quiet man from a small city trying to understand how the mind can know the world, and how we can live rightly within it.

Kant never traveled far from home. He lived almost his entire life in Königsberg, a Prussian city by the Baltic Sea, now Kaliningrad in Russia. He was not dramatic like Nietzsche or tormented like Schopenhauer. He was punctual, polite, and predictable. Yet from that ordinary routine came one of the most extraordinary revolutions in thought. He showed that the limits of knowledge are also the conditions of freedom.

His life was as precise as a clock, but his mind explored the deepest questions: What can I know? What should I do? What may I hope? And what is man?

Don’t forget to join our FREE book club!

We started a digital book club to study the great texts of Western Civilization — from Dante to Dostoevsky — together. Inside, you’ll get:

Live community book discussions (bi-weekly)

New, deep-dive literature essays every week

The entire archive of book reviews + our 100 great texts reading list

We’re back for our final Count of Monte Cristo discussion on October 14th at 12pm ET. Bring your thoughts, questions, and favorite passages!

Sign up below to attend — all paid members can join the live discussion up on stage…

Note: paid subscribers via Substack will automatically receive an access link for the live calls.

The Early Life

Immanuel Kant was born in 1724 in Königsberg, the fourth of nine children. His father was a saddler, a modest craftsman. His mother was devout, intelligent, and gentle, and from her he inherited both discipline and moral seriousness.

Kant’s family belonged to the Pietist movement, a branch of Protestantism that emphasized simplicity, piety, and the inner life. From an early age, he was trained to see life as a moral task. This moral intensity would stay with him, though later he would distance himself from the narrowness of dogmatic religion.

He studied at the Collegium Fridericianum, then entered the University of Königsberg in 1740. He studied philosophy, mathematics, and physics. His early writings were on natural science. He was fascinated by how the world worked, and his first publication was a treatise on the formation of the heavens. He speculated that the solar system might have arisen from a rotating nebula… a theory that modern science would later confirm in broad outline.

Yet even in these scientific writings, we see a philosophical question emerging: what makes knowledge possible? How does the mind grasp the world?

The Struggling Scholar

After his father died, Kant supported himself as a private tutor for several years. He lived frugally, reading, writing, and waiting for an academic position. He was shy but sociable, known for witty conversation and hospitality. He dressed neatly but modestly.

Finally, in 1755, he qualified to teach at the university as a Privatdozent, an unsalaried lecturer who lived on student fees. For the next fifteen years, he lectured on everything: logic, physics, mathematics, geography, anthropology, even fireworks. He was a brilliant teacher, clear and lively, unlike the dense writer he would later become.

But the great transformation of his thought was still to come. At this stage, he accepted the ideas of earlier philosophers… especially the rationalists like Leibniz and Wolff… who believed that reason alone could uncover the structure of reality. He also admired the empiricists like Newton and Hume, who grounded knowledge in observation.

When he read the Scottish philosopher David Hume, everything changed. Hume’s skeptical arguments shook him. Hume claimed that we never actually perceive cause and effect, only one event followed by another. The mind assumes connection, but it cannot prove it. This, Hume said, means reason cannot justify the certainty of science.

Kant later wrote that Hume “awoke me from my dogmatic slumber.” He realized that to save knowledge, he had to rethink the relationship between the mind and the world.

The Critique of Pure Reason

In 1781, after years of quiet work, Kant published his masterpiece: The Critique of Pure Reason. It is one of the most important books ever written, and one of the hardest to read. Its purpose was simple to state but profound in consequence: to answer the question of how knowledge is possible.

Before Kant, philosophy was divided between two camps. The rationalists said reason could discover truth independent of experience. The empiricists said all knowledge came from experience. Kant’s answer was both and neither. He said that while all knowledge begins with experience, not all of it arises from experience.

The mind, he argued, is not a passive mirror reflecting the world. It is active. It shapes experience through forms and categories… space and time, cause and effect, substance, quantity, and others. These are not learned from the world; they are built into the structure of the mind.

We never know the world as it is in itself… what Kant called the noumenal world. We know only the world as it appears to us… the phenomenal world… structured by our own mental framework.

This was Kant’s “Copernican revolution” in philosophy. Just as Copernicus showed that the sun does not revolve around the earth but the earth around the sun, Kant showed that knowledge does not conform to objects but objects conform to our way of knowing.

This may sound abstract, but its consequences are enormous. It means that reason has limits. We cannot know things beyond possible experience… not God, the soul, or the universe as a whole. But within those limits, we can have genuine, objective knowledge. Science is possible, but metaphysical speculation is not.

The Critique of Pure Reason was not immediately understood. Its first edition sold poorly. Even his friends were puzzled. Kant rewrote parts of it in a second edition in 1787, clarifying some ideas. Gradually, it became recognized as a turning point in philosophy.

The Second Critique: Morality

Kant did not stop with knowledge. He turned next to ethics. In 1788 he published The Critique of Practical Reason. If the first Critique asked what we can know, the second asked what we should do.

Here Kant argued that morality is not based on consequences or feelings but on duty. The moral law, he said, is discovered by reason itself. It commands unconditionally… not “if you want this, do that,” but “do this because it is right.”

This command is what he called the categorical imperative. It has several forms, but the most famous says: “Act only according to that maxim by which you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law.” In other words, before you act, ask yourself whether everyone could act the same way. If the answer is no, the action is wrong.

Another form says: “Act so that you treat humanity, whether in your own person or that of another, always as an end and never merely as a means.” Every person has dignity, not price. We must never use others merely for our purposes.

For Kant, moral worth lies not in success but in intention. A good will, acting from duty, is the only thing truly good without qualification. Even if all our efforts fail, if we act from duty, we have done right.

This ethics of duty may sound stern, but it also gives deep respect to human freedom. When we obey the moral law, we are not submitting to an external rule but to our own rational nature. Morality is autonomy… self-legislation. To be moral is to be free, because we act from our own reason, not from impulse or command.

The Third Critique: Beauty and Purpose

Kant’s third great work, The Critique of Judgment (1790), bridges the worlds of nature and freedom. It explores aesthetics and teleology… the experience of beauty and the sense of purpose in nature.

He asked: how is it that beauty moves us? When we judge something beautiful, like a sunset or a symphony, it gives pleasure without possession. It does not satisfy a desire but harmonizes our faculties of imagination and understanding. Beauty, for Kant, is “purposiveness without purpose.” It feels meaningful, though we cannot say exactly why.

In nature, we also see things as if they have purpose… as if living beings were designed. Kant said we cannot know if they truly are, but we must think of them as if they were, to understand them scientifically. Thus, beauty and life reveal the deep unity of mind and world.

The three Critiques… of Pure Reason, of Practical Reason, and of Judgment… form a whole. Together they explore truth, goodness, and beauty… the three great domains of philosophy.

The Daily Life

Kant became a professor at Königsberg and lectured for decades. His life was famously regular. He woke at the same hour, took the same walk each day, and was so punctual that townspeople said they could set their clocks by him.

He never married. He had friends but kept a strict routine. His home was orderly, his meals simple, his work steady. He avoided excess in everything. This discipline was not coldness but concentration. He wanted to live rationally, as he thought.

Though his life seemed uneventful, he lived through immense historical changes: the Enlightenment, the American Revolution, the French Revolution, the rise of Napoleon. He followed them all with interest but stayed focused on his work. He believed that human progress was possible only through moral and rational self-discipline.

The End

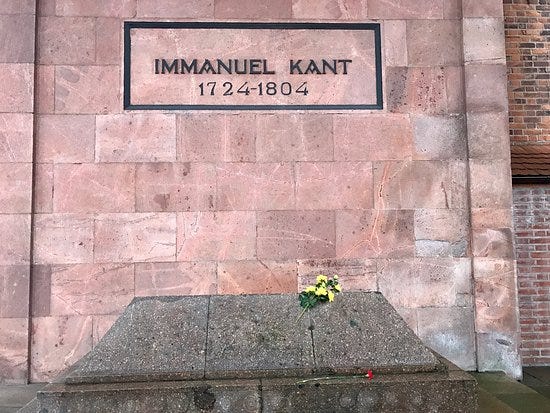

In his final years, Kant’s health declined. His memory failed, his strength waned, but he continued to work until he could no longer hold a pen steadily. He died in 1804 at eighty years old. His last words were said to be, “It is good.”

He was buried in Königsberg, where his tomb still stands, engraved with a line from the Critique of Practical Reason: “Two things fill the mind with ever new and increasing admiration and awe, the more often and steadily we reflect upon them — the starry heavens above me and the moral law within me.”

That sentence captures his life. He lived looking outward to the cosmos and inward to conscience.

The Legacy

Kant’s influence is hard to overstate. His “Copernican revolution” in philosophy became the foundation of modern thought. After him, philosophers could not ignore the mind’s active role in shaping experience.

Hegel, Fichte, and Schelling built their systems on Kant’s ideas. Schopenhauer, though critical, began with Kant’s distinction between appearance and thing-in-itself. Nietzsche rebelled against him but could not escape his shadow.

In ethics, Kant’s idea of human dignity became central to modern moral philosophy, law, and human rights. The concept that every person must be treated as an end in themselves echoes through constitutions and charters around the world.

In art, his ideas about beauty as disinterested pleasure influenced aesthetics for centuries. In science, his framework for understanding the limits of reason prefigured later debates about relativity, perception, and the observer’s role.

Even his humility… his insistence that reason must know its limits… became a model for intellectual honesty. He taught that there are things we can know, things we must believe, and things we must simply act upon in faith.

Lessons from Kant

From Kant’s life and philosophy, several lessons emerge.

1. The importance of limits.

Kant teaches that freedom is not doing whatever we please but living within rational limits. Knowledge is powerful precisely because it recognizes where it ends. We cannot know the ultimate nature of reality, but within our sphere, we can know truly.

2. The dignity of duty.

Kant’s ethics is demanding, but it gives moral life depth. We act rightly not because we expect reward but because it is right. This gives each person infinite worth.

3. The unity of mind and world.

For Kant, experience is not raw data but the meeting of the world and the mind. Reality is not something completely foreign to us, because the very structure of our mind shapes it. That insight still underlies cognitive science and philosophy today.

4. The quiet power of discipline.

Kant’s life shows that greatness need not be dramatic. From a small city, through steady labor, came a revolution in thought. His example reminds us that steady attention can move the world.

5. The balance of awe and reason.

Kant’s final line about the heavens above and the moral law within shows that he was not only a thinker but a man of wonder. For all his rigor, he saw life as something to be respected and marveled at.

Why Kant Still Matters

His ideas endure because they speak to permanent human questions.

We still struggle to understand how our minds shape reality. We still wrestle with moral responsibility in a world of shifting values. We still seek beauty that feels meaningful but not possessive. Kant gives tools for thinking about all of these.

He also reminds us that reason and morality are not enemies of faith or feeling. They are what make them human. He believed religion, properly understood, is morality extended by hope… not superstition but reverence for the moral order of the world.

His philosophy is demanding, but it gives dignity to reason, meaning to duty, and space for wonder. It tells us that we live in a moral universe, even if we cannot see all its depths.

Conclusion

Immanuel Kant lived his whole life in one city, walked the same path each day, and never married or traveled far. Yet his mind traveled farther than almost anyone’s. He built a system that encompassed science, ethics, and art, showing their unity in the structure of human reason.

He told us we cannot know things beyond experience, but we can live rightly within experience. He showed that freedom is obedience to the law we give ourselves. He taught that beauty reconciles us with the world. And he lived a life that proved quiet discipline can change the course of thought.

Kant’s greatness lies not in comforting us but in clarifying the terms of our existence. He drew the boundaries of knowledge but within those boundaries found reason, morality, and beauty.

That is Immanuel Kant… the man who taught the modern world its limits, and by doing so, gave it its freedom.

Really proud of this piece — tons of research went into it. Hope you enjoy it!

Absolutely loved this article, you did an awesome job! Beyond some quotes, and knowing he was from Königsberg, I didn't know anything about Kant. You did well to also present him in his actual life, it speaks to us more deeply, makes him "more human"