The Modern Prophet

Doubt, truth, and the search for greatness

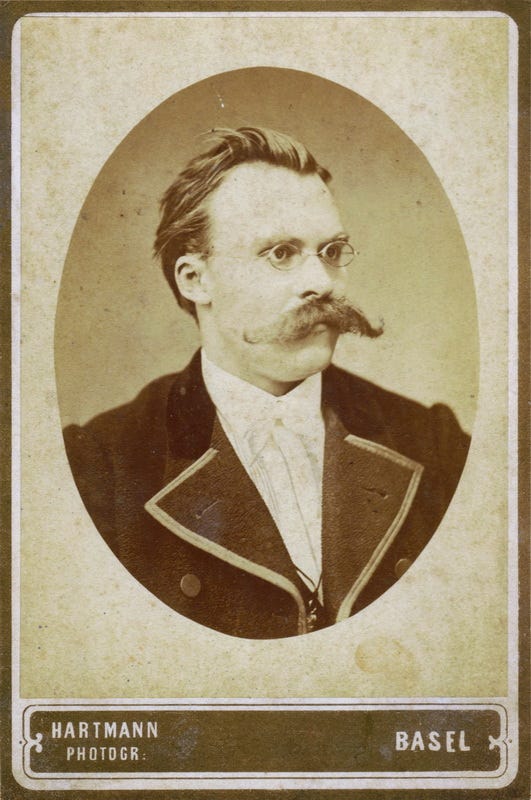

Friedrich Nietzsche wrote like a man who was trying to set the world on fire.

He asked questions that still unsettle people. What happens when belief fades? What does life mean when there is no God to give it meaning? How can a person live with courage in a world without certainty?

He was born in 1844 in a small village in Germany. His father was a Lutheran pastor who died when Nietzsche was five. That loss left a mark. He grew up in a house full of women… his mother, grandmother, and sister… all devoted and pious. Religion was everywhere in his childhood. It gave him comfort and order. Later, it would become the first thing he tore apart.

As a boy, he was quiet and serious. He loved music and poetry. He read the Greeks and admired their tragic heroes. He wanted to be both a scholar and an artist, someone who lived ideas rather than just studied them. At university, he was brilliant. He became a professor of classical philology at twenty-four, one of the youngest in Europe. His future seemed secure. But he soon realized that he was not made for academic life. He wanted to write, not lecture. He wanted to think freely, without permission…

Don’t forget to join our FREE book club!

We started a digital book club to study the great texts of Western Civilization — from Dante to Dostoevsky — together. Inside, you’ll get:

Live community book discussions (bi-weekly)

New, deep-dive literature essays every week

The entire archive of book reviews + our 100 great texts reading list

Our next discussion on Confessions by Saint Augustine is on November 11th at 12pm ET. Bring your thoughts, questions, and favorite passages!

Sign up below to attend — all paid members can join the live discussion up on stage…

Note: paid subscribers via Substack will automatically receive an access link for the live calls.

The Break with Tradition

Nietzsche’s first book, The Birth of Tragedy, was published in 1872. It was strange and bold. Instead of dry analysis, it read like a vision. He argued that Greek tragedy came from the tension between two forces: the Apollonian, which seeks order and beauty, and the Dionysian, which embraces chaos and passion. Great art, he said, comes from balancing both.

The book shocked scholars. They called it unscientific and reckless. Nietzsche did not care. He was already turning away from the academic world. He believed that the Greeks had faced the darkness of life without illusion. They had created art not to escape suffering, but to affirm it. That idea would stay with him forever.

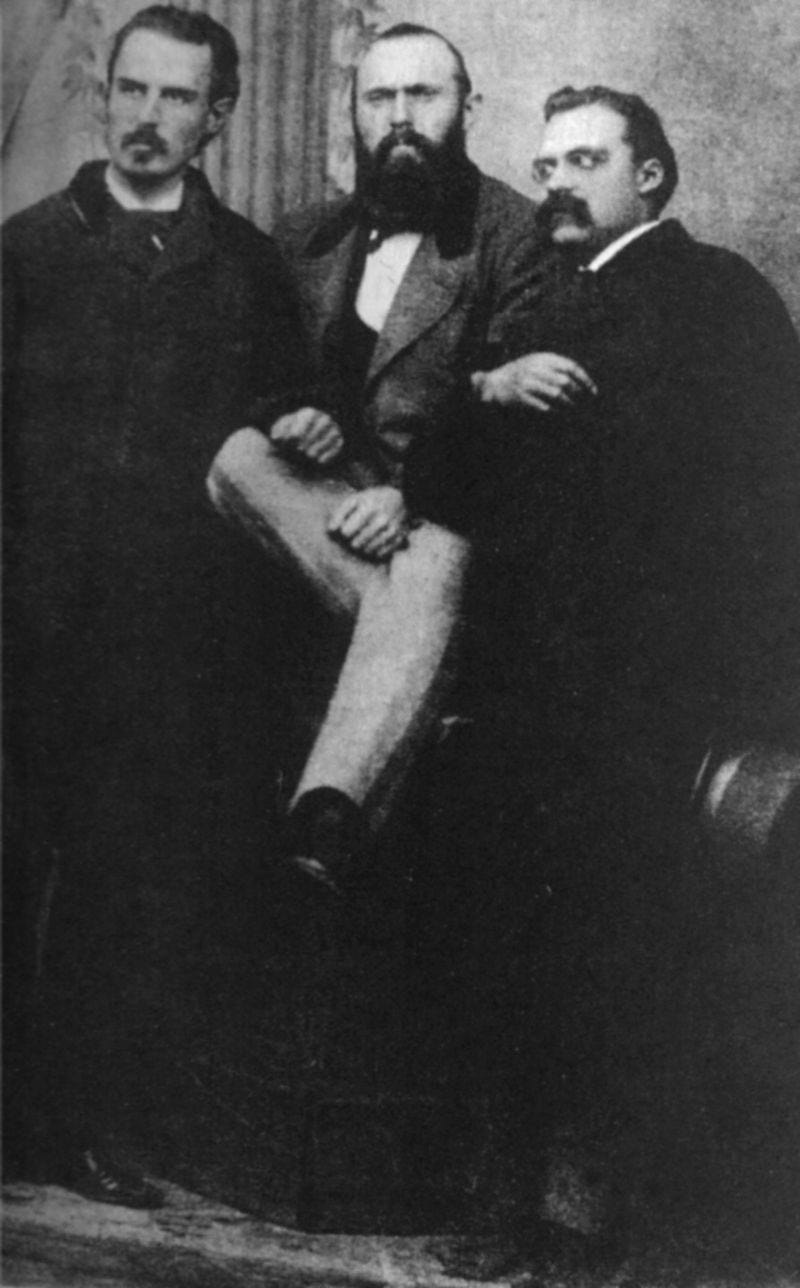

Soon after, his friendship with the composer Richard Wagner began to shape his life. Nietzsche admired Wagner as a modern genius who combined art and myth, reason and emotion. He saw in Wagner the possibility of a new cultural rebirth. But as time passed, he grew disillusioned. Wagner’s growing nationalism and religious symbolism disgusted him. Their friendship ended bitterly. For Nietzsche, it was another step away from faith in anyone but himself.

The Philosopher of Crisis

By his mid-thirties, Nietzsche’s health was failing. He suffered from migraines, insomnia, and stomach pain. He resigned from his university post and lived alone, moving from one small town to another in Switzerland and Italy. He wrote during the mornings and walked for hours in the afternoons. He was almost always sick, poor, and lonely.

But his isolation gave him freedom. Between 1878 and 1888, he wrote the works that made him famous: Human, All Too Human, Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Beyond Good and Evil, and The Genealogy of Morality. Each book is different in tone, but together they form one long meditation on what happens when belief collapses.

He saw clearly that Europe was losing its faith. Science had undermined religion, and politics had replaced conviction with comfort. The old values… humility, obedience, charity… no longer made sense in a world that no longer believed in God. But Nietzsche did not celebrate this loss. He mourned it. He saw what few others did: that without faith, people would not become free. They would become empty.

His most famous line… “God is dead”… is often misunderstood. Nietzsche did not mean that a divine being had literally died. He meant that belief in God had died in the hearts of modern people. The world had lost its highest value. What would replace it was unknown.

For Nietzsche, this was both a tragedy and an opportunity. The death of God created a vacuum, but also a challenge. If the old foundation was gone, humanity had to create a new one. Life could still have meaning, but that meaning would have to be made by human hands.

The Will to Power

At the center of Nietzsche’s thought is a single idea: the will to power. He believed that every living thing strives to expand, to express its strength, to become more than it is. This drive, not survival or pleasure, is the essence of life. In humans, the will to power becomes creative. It pushes people to make, to shape, to overcome.

He admired strength, but not the kind that dominates others. True strength, for Nietzsche, was mastery over oneself… the ability to endure suffering and turn it into something beautiful. Weakness, in his eyes, was not lack of power but lack of honesty. He despised those who hid their resentment behind virtue.

He saw much of modern morality as a disguise for envy. In The Genealogy of Morality, he argued that Christian values had once been revolutionary. They had given meaning to the powerless. But over time, they turned into a system that glorified weakness and condemned strength. What began as faith in love had become a culture of guilt.

Nietzsche wanted to free humanity from that guilt. He wanted people to affirm life as it is… full of pain, risk, and loss… instead of clinging to comforting illusions. His ideal figure, the Übermensch, or “overman,” represents this freedom. The overman is not a tyrant or a god. He is someone who has created his own values, who stands alone and says yes to existence even when it hurts.

Thus Spoke Zarathustra

Nietzsche’s most poetic work, Thus Spoke Zarathustra, tells the story of a prophet who comes down from a mountain to teach humanity how to live after the death of God. It is not a novel in the usual sense. It reads like scripture, full of parables and aphorisms.

Zarathustra preaches the coming of the overman and urges people to overcome their smallness. He tells them that life is not a problem to be solved but a mystery to be affirmed. He warns against the “last man,” the comfortable, mediocre being who wants only safety and pleasure.

Nietzsche’s vision is hard and demanding. He believed that true joy comes not from comfort but from struggle. The person who says “yes” to life, including its suffering, is the one who lives most fully.

He called this attitude “amor fati,” the love of fate. To love one’s fate means to accept everything that happens, even pain and failure, as necessary and good. It means to look at your life and say, “I would live it again.”

The Eternal Return

One of Nietzsche’s strangest and most powerful ideas is the eternal return. Imagine, he said, that you must live your life again and again forever. Every joy, every mistake, every sorrow will happen exactly the same way. Would you curse this fate, or would you embrace it?

For Nietzsche, this was not a literal belief but a test. If you could affirm your life even under that thought, you were free. You had overcome resentment. You had learned to love existence completely.

The eternal return is a way of measuring one’s strength. Most people, he thought, would recoil from it. They would wish to change or erase parts of their lives. But the strong would see it as liberation. To live as if you would will everything again… that was Nietzsche’s definition of greatness.

The Collapse

By 1889, Nietzsche’s body and mind gave out. In Turin, he suffered a mental breakdown. One story says that he saw a horse being beaten in the street, threw his arms around its neck, and collapsed in tears. After that, he never recovered.

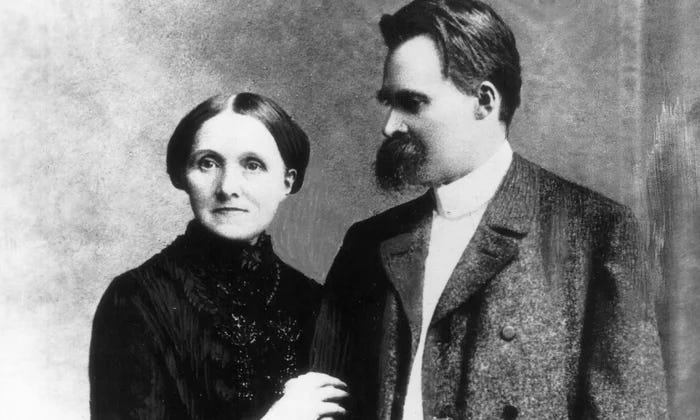

His mother cared for him until her death, and then his sister took over. He spent the last eleven years of his life in silence, unable to write or recognize anyone. He died in 1900 at fifty-five.

His sister, Elisabeth, edited and distorted his writings after his death. She had nationalist sympathies and tried to link Nietzsche’s philosophy to German militarism. Decades later, the Nazis twisted his words to justify their ideology. Nietzsche would have despised them. He hated nationalism and herd thinking of any kind. His philosophy was about self-overcoming, not domination.

The Legacy

Nietzsche’s influence on modern thought is immense. He shaped writers, psychologists, and artists across generations. Freud took from him the idea that human motives are deeper than reason. Existentialists like Sartre and Camus saw him as the first to face the absurdity of life with honesty. Even those who disagree with him owe him something. He forced everyone to confront the question of meaning without hiding behind tradition.

What makes Nietzsche lasting is not his conclusions but his courage. He was willing to face despair directly. He called himself a psychologist of the soul. He wanted to know why people cling to beliefs, why they lie to themselves, why they fear freedom. His goal was not destruction but renewal. He wanted to clear away illusions so something stronger could be built in their place.

Nietzsche’s writing feels modern because he wrote about problems that still haunt us: the emptiness of comfort, the anxiety of freedom, the temptation to avoid responsibility by blaming society or fate. He believed that the only honest path was through struggle.

The Man Behind the Ideas

It is easy to think of Nietzsche as pure intellect, but he was deeply human. He loved music and composed small piano pieces. He admired Beethoven, who like him lived with pain but turned it into creation. He was shy, polite, and often lonely. He longed for friendship and love but rarely found either.

His letters reveal a man torn between pride and tenderness. He cared for his friends, but his honesty often drove them away. He could not pretend. That honesty made him tragic but also noble.

He lived simply, walking for hours each day, eating sparingly, and writing in bursts of energy that left him exhausted. His books were often ignored or mocked during his life. Only after his death did people begin to see how deep they were.

The Modern Prophet

Nietzsche saw earlier than anyone that modernity would not end in peace but in confusion. He predicted a time when people would have more comfort and less meaning. He saw how technology and progress would create wealth but not purpose. He warned that when people stop believing in something higher, they do not become liberated; they drift.

He imagined a future where boredom, cynicism, and resentment would replace faith. His description of the “last man,” content, safe, and empty, feels more accurate now than ever. Nietzsche’s call to greatness was a warning against that kind of smallness.

To read him today is to feel challenged. He does not tell you what to believe. He tells you to look in the mirror and ask whether you are living fully. He tells you to stop blaming the world for your weakness and to turn suffering into strength.

The Courage to See Clearly

What Nietzsche wanted above all was clarity. He thought that most people live behind masks… of morality, of religion, of ideology. They lie to themselves to avoid seeing how uncertain life really is. He believed that courage begins with honesty. To face the truth of existence without illusion is painful, but it is also freeing.

He did not want to destroy faith, only hypocrisy. He did not reject meaning, only the idea that it could be handed down ready-made. He wanted people to create their own values, not inherit them. That is why he is often called a philosopher of freedom.

But freedom, for Nietzsche, was not pleasure. It was responsibility. To be free meant to bear the weight of your choices without excuses. It meant to live with intensity, to strive for excellence, and to accept the cost of both.

Closing Reflection

Nietzsche’s life was short and full of pain, but he turned that pain into one of the most powerful philosophies ever written. He saw that truth is often unbearable, but he chose it anyway. He believed that beauty and greatness are born not from comfort but from struggle.

He once wrote, “One must still have chaos in oneself to give birth to a dancing star.” That line captures everything he stood for. To live well is not to avoid suffering, but to use it. To create meaning out of it. To say yes to life in all its confusion and terror.

Nietzsche was not asking people to worship strength for its own sake. He was asking them to be strong enough to face reality and still love it. That is what he meant by the overman, and that is what he meant by amor fati.

He remains one of the few writers who make you feel braver simply by reading him. He does not comfort you. He demands something from you. And that demand… to live with eyes open, to turn pain into power, to create meaning in a world without guarantees… is why his voice still feels alive more than a century later.

Thank you for such an interesting and incisive homage.

Excellent, thank you so much!