The Meaning of History

A story of reason, conflict, and becoming

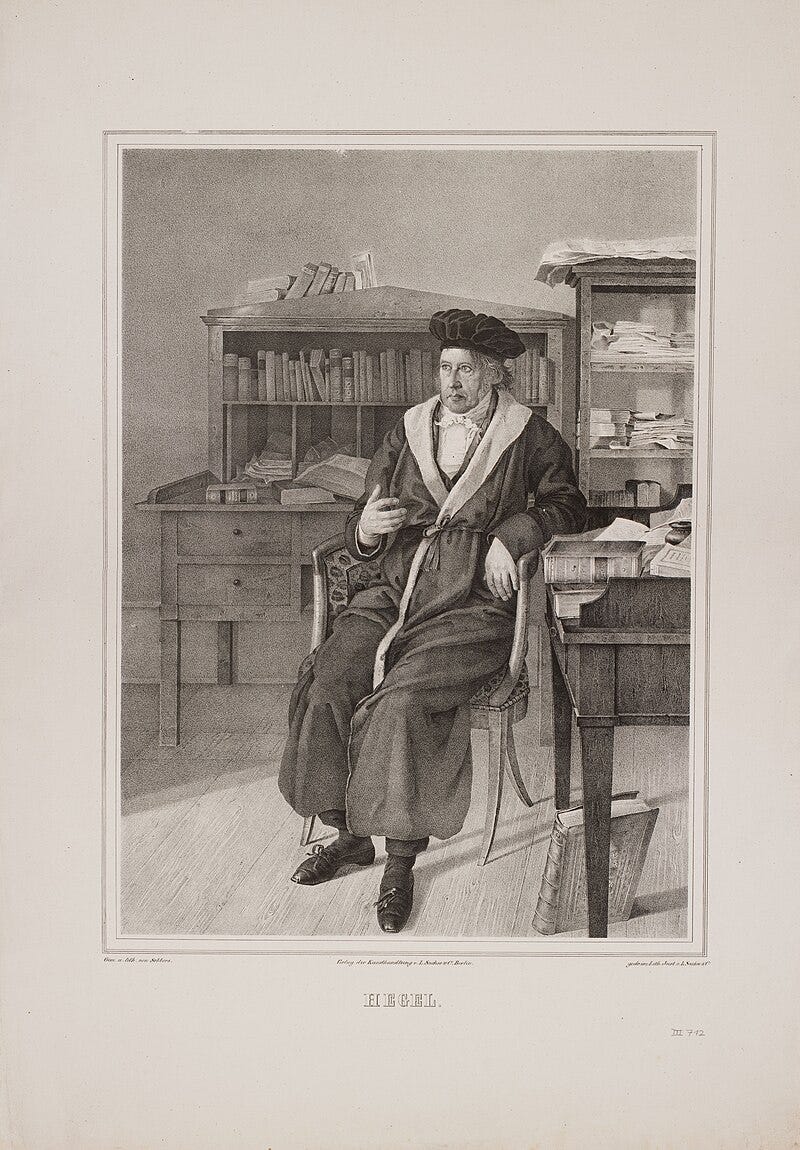

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel is one of the most difficult philosophers to read. His sentences are long, his words heavy, his books intimidating. Many have opened his Phenomenology of Spirit or Science of Logic and given up in despair. Even professional philosophers joke about his obscurity. Yet despite this, Hegel remains one of the most influential thinkers of modern times.

His ideas shaped theology, politics, literature, art, and philosophy. Marx developed his theory of history out of Hegel. Kierkegaard defined himself against him. Nietzsche reacted to him. Later, whole schools of thought… existentialism, phenomenology, critical theory… formed in dialogue with him. Hegel is like a mountain in the landscape of thought. You cannot avoid him.

But why? What did Hegel actually say? And why has it mattered so much? The answer is not simple. But we can at least trace the outlines. Hegel believed that history itself has meaning, that human freedom unfolds over time, and that contradictions are not failures but the very engine of progress. He called this process the unfolding of Spirit, or Geist, through history.

To see how he arrived there, let us look at his life, his work, and his legacy.

Don’t forget to join our FREE book club!

We started a digital book club to study the great texts of Western Civilization — from Dante to Dostoevsky — together. Inside, you’ll get:

Live community book discussions (bi-weekly)

New, deep-dive literature essays every week

The entire archive of book reviews + our 100 great texts reading list

We’re back for our final Count of Monte Cristo discussion on October 14th at 12pm ET. Bring your thoughts, questions, and favorite passages!

Sign up below to attend — all paid members can join the live discussion up on stage…

Note: paid subscribers via Substack will automatically receive an access link for the live calls.

The Beginning

Hegel was born in 1770 in Stuttgart, in the Duchy of Württemberg. He grew up in a middle-class family. His father was a civil servant. His mother died when he was thirteen, leaving a deep mark.

As a boy he was studious. He read voraciously, copying passages from history, philosophy, and literature. He was drawn to reason and system. He attended the seminary in Tübingen, where he studied theology. There he met two other young men who would also become famous: Friedrich Hölderlin, the poet, and Friedrich Schelling, the philosopher. The three became close friends. They read Rousseau and the Greeks. They planted a “Tree of Liberty” to celebrate the French Revolution. They dreamed of freedom and transformation.

Hegel was not a fiery revolutionary, but he absorbed the spirit of the age. Europe was being shaken by revolution, war, and change. The old order was collapsing. The question of how to make sense of history burned in him.

The Struggles of Early Life

After leaving the seminary, Hegel worked as a private tutor in Switzerland and Frankfurt. These were not glamorous years. He taught children, read widely, and wrote in notebooks. He was poor, obscure, and unsure of his future. He wrote essays on religion, criticizing empty ritual and dreaming of a faith united with freedom. He admired the Greeks and longed for a renewal of spirit in modern life.

When his father died in 1799, Hegel inherited a small sum that allowed him to pursue philosophy full time. He joined Schelling at the University of Jena, the center of German thought. There he finally began to write and publish.

The Phenomenology of Spirit

In 1807 Hegel published The Phenomenology of Spirit, his first great work. It is one of the most challenging books ever written, but also one of the most important. In it, Hegel traces the journey of consciousness… from simple sense-perception to self-consciousness, to reason, to spirit, to absolute knowing.

The book is not just abstract. It is filled with vivid episodes. The most famous is the “master and slave” dialectic. Hegel describes how self-consciousness arises in struggle. Two selves confront each other. One becomes master, the other slave. At first the master seems victorious. But in fact the slave, through work and transformation of the world, develops deeper self-consciousness. Dependence turns to independence.

This is an example of Hegel’s method. He shows how contradictions drive development. Every position contains its opposite, and out of the conflict emerges a higher unity. This process is called dialectic. It is not a simple formula of thesis, antithesis, and synthesis, as people often say, but rather the movement of thought and reality through contradiction to greater truth.

The Phenomenology ends with the idea of Spirit recognizing itself in history, philosophy, art, and religion. It is both an account of how consciousness develops and a kind of initiation for the reader, guiding them through stages of awareness.

The Hard Years

Despite its brilliance, the book did not make Hegel famous. The Napoleonic wars disrupted everything. Hegel lost his position in Jena when the French army occupied the city. He worked briefly as a newspaper editor, then as a headmaster of a gymnasium in Nuremberg. These were years of practical labor, not glory. He married, had children, and managed a school. He continued to write at night.

In these years he produced his Science of Logic, an immense work of pure philosophy. It is perhaps his most difficult book. In it he analyzes categories of thought… being, nothing, becoming, essence, concept, and so on. He shows how each category contains contradictions that lead to the next. It is a philosophy of pure reason, abstract and demanding. Few read it outside specialists, but it is central to his system.

The Professor

Eventually Hegel’s reputation grew. He became a professor at Heidelberg, then at Berlin, the most important university in Germany. There he attracted many students and became a public intellectual. By the 1820s he was recognized as the leading philosopher of his time.

His lectures covered everything: philosophy of history, philosophy of religion, aesthetics, politics. He systematized knowledge. He spoke of philosophy as the “owl of Minerva” that flies at dusk, meaning that philosophy understands reality only after it has already unfolded. He was both revered and ridiculed for his dense style and grand ambition.

Philosophy of History

One of Hegel’s most enduring contributions is his philosophy of history. He argued that history is rational, that it has a direction and meaning. It is the unfolding of freedom. In ancient times only one was free… the king. In classical times some were free… the citizens. In modern times, all are recognized as free. History is the progress of the consciousness of freedom.

This was a bold claim. It meant that wars, revolutions, and struggles are not meaningless chaos but part of a larger development. Even tragedy contributes to progress. Napoleon, Hegel said, was “the world spirit on horseback.” He saw in Napoleon the embodiment of history moving forward, sweeping away the old order.

This view of history influenced countless thinkers. It inspired both liberals, who saw progress in constitutional government, and radicals like Marx, who recast Hegel’s dialectic in materialist terms. It also provoked critics like Kierkegaard, who felt Hegel overlooked the individual.

Philosophy of Spirit

Hegel’s central idea was Spirit, or Geist. Spirit is not a ghostly entity but human consciousness, culture, and freedom in its collective unfolding. Spirit develops through art, religion, and philosophy. In art we see truth in sensuous form. In religion we see truth in images and stories. In philosophy we see truth in pure thought.

Spirit is the unity of subject and object, mind and world. Hegel opposed dualisms that separate thought and reality. For him, reality is rational and reason is real. To understand the world is not to impose concepts on it but to recognize that it is structured by reason itself.

Politics

Hegel also wrote about politics in his Philosophy of Right. He defended the modern state as the realization of freedom. He believed true freedom is not just doing whatever one wants but living in ethical life… what he called Sittlichkeit… the harmony of individual and community. Family, civil society, and the state are stages of this.

He supported constitutional monarchy, not revolution. He feared chaos and saw the state as the rational order of freedom. Some later accused him of justifying authoritarianism, but his defenders argue he sought a balance of freedom and order.

Religion

Hegel saw Christianity as the highest religion, because it expressed the unity of divine and human, infinite and finite, in the figure of Christ. For him, religion was truth in the form of representation, while philosophy was the same truth in the form of concept. He did not dismiss religion but tried to show its rational meaning.

This deeply influenced theology, especially the so-called “Left Hegelians” who secularized his ideas, and the “Right Hegelians” who defended Christianity with his concepts.

Death and Legacy

Hegel died in 1831 in Berlin, probably of cholera, at the age of sixty-one. At the time he was at the height of fame. His students published his lectures posthumously, spreading his influence further.

His legacy is vast. Marx turned his dialectic upside down, making it materialist rather than idealist. Kierkegaard attacked his system and insisted on individual existence. Nietzsche mocked his abstractions. Yet all were shaped by him. In the twentieth century, phenomenology, existentialism, structuralism, and postmodernism all wrestled with Hegel.

Even today, his philosophy of history provokes debate. Is history meaningful? Does freedom progress? Are contradictions the engine of development? These questions still animate philosophy and politics.

Lessons from Hegel

What can we, ordinary readers, learn from Hegel?

First, that contradiction is not failure. We often think conflict means something has gone wrong. Hegel teaches that conflict is how growth happens. Opposites push against each other and produce higher unity. This can apply to ideas, relationships, and societies.

Second, that history matters. Our lives are not isolated but part of a larger story. Freedom is not just a personal matter but something that has been struggled for across centuries. Seeing ourselves as part of history can give both humility and purpose.

Third, that reason is real. In a world that often seems chaotic, Hegel believed that reality has structure, that it can be understood. Even if we doubt his system, his confidence in reason challenges our despair.

Fourth, that philosophy is not just private reflection but engagement with culture, politics, and spirit. Philosophy asks not only “what is true” but also “what is our time.”

Why Hegel Still Matters

Hegel is hard to read. But once you grasp the outlines, his vision is compelling. He saw life as process, becoming, development. Nothing is static. Everything moves through contradiction toward greater freedom. This is why his influence is so wide. He gives a way to think about change, history, and meaning.

We may not accept all his claims. History may not be as rational as he thought. Freedom may not advance so smoothly. But the idea that struggle and contradiction can lead to growth remains powerful. His philosophy helps us see beyond chaos to process, beyond conflict to development.

Conclusion

Hegel lived through revolution, war, and change. He saw Napoleon ride through Jena and called him the world spirit on horseback. He believed history itself has meaning, that reason unfolds through time, that freedom grows through struggle. He wrote in dense prose, but his ideas reshaped philosophy.

Schopenhauer hated him. Kierkegaard resisted him. Marx transformed him. Nietzsche mocked him. But none could ignore him. He remains a mountain on the landscape of thought.

His life shows that philosophy is not just abstract puzzles but an attempt to understand our world, our history, and our freedom. He believed reality is not fixed but becoming, and that Spirit finds itself through contradiction.

That is Hegel: the philosopher of history and Spirit, the thinker of contradiction and freedom, the man who tried to see reason in the whole.

Such a (thought)provoking idea that the modern age has a deeper self-conscious grasp of God than the time of Christ himself. Not because Christ was incomplete, but because the >meaning< of the Incarnation could only unfold historically. Wouldn’t agree with Hegel on this, but worth grappling with.

This was a great read and I thank you.