The Man Who Said Life Is Suffering

A story of pessimism, truth, and the search for peace

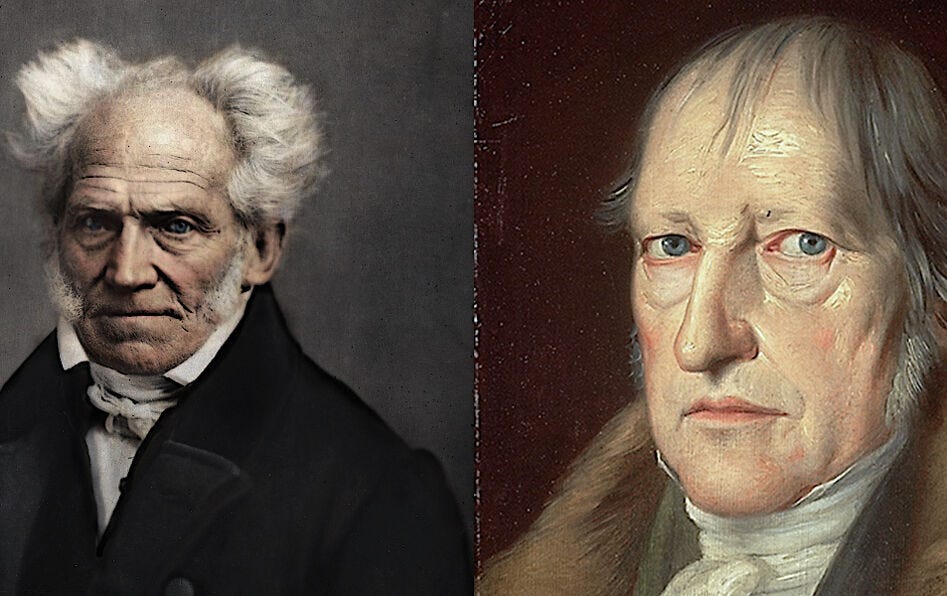

Arthur Schopenhauer is one of those rare philosophers whose reputation has grown stronger over time. When he was alive, he lived in obscurity. His lectures were almost empty. His books sold poorly. He was overshadowed by Hegel, whose sweeping optimism about history and reason dominated German philosophy in the early nineteenth century. Schopenhauer railed against Hegel and called him a fraud. The academic world dismissed him as bitter and eccentric.

Yet in the decades after his death, Schopenhauer’s work caught fire. Artists, writers, and musicians found in him a voice that spoke more truly than the optimistic systems of his rivals. Nietzsche called him an educator. Wagner built operas under his influence. Tolstoy and Dostoevsky resonated with his view of suffering. Freud echoed him in psychology. Even today his phrases are quoted in self-help books, his ideas reframed in discussions of desire, happiness, and mindfulness.

What makes Schopenhauer last is not that he gave people comfort but that he gave them honesty. He looked at life without illusions. He said plainly what most suspect deep down: that life is hard, that desire never ends, and that happiness is fleeting. Yet he also pointed toward ways of living with this reality… through art, compassion, and a certain kind of resignation.

Let us walk through his life, then his philosophy, and finally the lessons we can still draw from him…

Don’t forget to join our FREE book club!

We started a digital book club to study the great texts of Western Civilization — from Dante to Dostoevsky — together. Inside, you’ll get:

Live community book discussions (bi-weekly)

New, deep-dive literature essays every week

The entire archive of book reviews + our 100 great texts reading list

We’re back with our second Count of Monte Cristo discussion on September 30th at 12pm ET. Bring your thoughts, questions, and favorite passages!

Sign up below to attend — all paid members can join the live discussion up on stage…

Note: paid subscribers via Substack will automatically receive an access link for the live calls.

The Beginning

Arthur Schopenhauer was born in 1788 in Danzig, a port city on the Baltic Sea, now Gdańsk. His father, Heinrich Floris, was a wealthy merchant. His mother, Johanna, was imaginative and social, later a successful novelist and salon host. Arthur inherited intelligence from both, but his temperament leaned more toward the stern seriousness of his father.

The family moved to Hamburg when Arthur was a boy. His father wanted him to continue in trade and prepared him with travel. Arthur was taken on journeys across Europe, seeing France, England, Switzerland, and Italy. He learned languages and gained a sense of the wider world. But he did not love commerce. He found the business world shallow and longed for study and reflection.

When Arthur was seventeen, his father died… probably by suicide. This left a deep mark. Arthur received an inheritance that allowed him to live independently. He turned away from trade and toward study. His mother began hosting literary salons in Weimar, and Arthur sometimes joined, but their relationship was strained. Johanna was lively and sociable, Arthur brooding and sharp-tongued. They quarreled often and eventually broke off contact.

The Student

Arthur studied medicine, then philosophy, at universities in Göttingen and Berlin. He was drawn to the ancients, especially Plato, who gave him the idea of eternal forms, and to moderns like Kant, who had shown the limits of reason. Kant’s “thing-in-itself”… the reality behind appearances captivated him. Schopenhauer wanted to push further: what is the thing-in-itself? What lies behind the world we see?

He also read Eastern texts. Through translations of the Upanishads and Buddhist writings, he found ideas of suffering, desire, and release that resonated with him. This was unusual at the time, when most German philosophers focused only on European sources.

He earned his doctorate in philosophy in 1813. His dissertation, On the Fourfold Root of the Principle of Sufficient Reason, was the seed of his later system. It examined how everything in the world is connected by cause, reason, and necessity. Already he was moving toward a vision of the world as ordered by forces deeper than human thought.

The Philosopher in Obscurity

In 1818, at thirty years old, Schopenhauer published his major work: The World as Will and Representation. He believed this book would make his name. It did not. It was largely ignored.

The book was radical. It said the world we perceive is representation, shaped by our minds, much like Kant had argued. But behind representation, behind all appearances, lies the “Will.” Not will in the sense of conscious choice, but a blind striving, a drive to exist, to survive, to reproduce. This Will is the essence of reality. Everything… animals, plants, humans, even nature itself… is the manifestation of this Will.

This was not a comforting picture. It meant that life is driven by a restless, endless force. Desire never ends. When one wish is satisfied, another arises. Happiness is only temporary relief from desire, quickly replaced by boredom or new craving. Life oscillates between pain and boredom.

It is easy to see why this view was not popular. It was the opposite of the optimism of Hegel, who taught that history was progressing toward freedom and reason. Schopenhauer rejected this and saw only endless striving.

He began teaching in Berlin, scheduling his lectures at the same hour as Hegel’s. Almost everyone went to Hegel. Schopenhauer’s hall was nearly empty. This humiliation deepened his bitterness. He left academia and lived quietly in Frankfurt, supported by his inheritance, writing, studying, and walking his beloved poodles.

The Philosopher of Pessimism

Though ignored at first, Schopenhauer’s ideas slowly spread. His writing style helped. Unlike many philosophers, he wrote clearly, forcefully, even wittily. He did not hide behind jargon. He insulted his rivals, mocked academics, and wrote sentences that could be remembered.

The core of his philosophy remained his vision of the Will. Everything is driven by it. Human life especially shows its futility: we desire, strive, struggle, and die. History does not progress. Human nature does not improve. Civilizations rise and fall. Suffering continues.

Yet he did not stop at despair. He looked for ways to cope. He offered three.

First, art. In art we step outside of striving for a moment. When we contemplate beauty, whether in painting, music, or literature, we forget our desires and see the world as pure representation. Music especially, he said, reveals the Will directly, expressing longing without words.

Second, compassion. Though life is suffering, we can soften it by caring for others. Compassion is the basis of morality, because we recognize that others are driven by the same Will and suffer as we do.

Third, renunciation. Ultimately the deepest peace comes not from fulfilling desire but from quieting it. He admired saints, ascetics, and figures in Buddhism who turned away from striving. In this he saw the possibility of release from the tyranny of the Will.

The Later Recognition

In the 1850s, Schopenhauer’s work finally gained attention. A new generation of readers, tired of Hegelian abstraction, discovered his clarity. Artists and writers found in him a philosophy that matched their sense of the world. Richard Wagner used his ideas in his operas. Writers like Thomas Mann, Leo Tolstoy, and Friedrich Nietzsche took inspiration, even when they later broke away.

Schopenhauer, once ignored, became famous late in life. His books sold well. He was sought out by admirers. He enjoyed recognition but never lost his edge of bitterness. He died in 1860 in Frankfurt, at seventy-two, leaving behind the image of the solitary philosopher who spoke uncomfortable truths.

The Pessimist Who Helps

It is ironic that a philosopher of pessimism can help people. But sometimes what helps is not optimism but honesty. Schopenhauer did not flatter us. He said life is hard and full of disappointment. Yet in facing this, we may find a steadier peace. We stop expecting perfect happiness. We stop being shocked by suffering. We learn to value art, compassion, and quietness.

Many who read him find not despair but clarity. His words match their own experience. They feel less alone in their struggles. And in the space left by abandoned illusions, they find freedom.

Why He Still Matters

Today, in a world of constant stimulation and consumerism, Schopenhauer is strangely modern. He warned that desire never ends, that chasing satisfaction only brings more craving. In an age of advertising and social media, this is more relevant than ever.

He also bridges East and West. His use of Indian philosophy anticipated the later Western interest in Buddhism and meditation. His idea that peace comes from quieting desire echoes practices of mindfulness today.

And he reminds us that philosophy is not just abstract. It is about life, suffering, and how to endure. His style, clear and sharp, still cuts through the noise.

Conclusion

Arthur Schopenhauer lived a lonely life. He quarreled with his mother, lost to Hegel, lectured to empty rooms, and lived with dogs for company. Yet out of this solitude he wrote words that outlived both rivals and critics. He told us life is suffering, desire endless, happiness fleeting. But he also pointed to art, compassion, and renunciation as ways to find peace.

His philosophy is not cheerful. But it is real. And sometimes reality is what we need most.

That is why Schopenhauer endures: not because he promised us what we wanted to hear, but because he told us what we already knew in our hearts.

.

Schopenhauer, to me, stands as a portrait of the modern soul.

Torn between a longing for the transcendent and the grip of blind desire.

His philosophy paints humans as microcosms driven by will, echoing the fallen world of Genesis.

Beauty offers a fleeting redemption, especially music, which he saw as the pure voice of the world’s essence.

In this way, art becomes a kind of sacrament, a shadow of paradise in the midst of suffering.

Symbolically, he embodies both the despair of a world lost in multiplicity and the fragile hope that glimpses of truth can still pierce the veil.

Following these glimpses might lead us back to Eden - Schopenhauer lacked the optimism to follow them.

Schopenhauer’s ideas are very closely aligned with Buddhist philosophy. It is very evident that he studied Buddhism and incorporated its teachings into his writings.