The Long Road to Grace

A restless mind, a searching heart, and the long road to grace

Saint Augustine lived at the end of the ancient world. Rome was falling apart. The old gods were fading. New beliefs were spreading. He was born in that world of confusion and change. He grew up smart, ambitious, and restless. He wanted success and truth at the same time, and he chased both with equal hunger.

What makes Augustine’s life powerful is how real it feels. He wasn’t born wise or holy. He learned slowly, through mistakes and disappointment. His life is a record of how a person learns what to love…

Don’t forget to join our FREE book club!

We started a digital book club to study the great texts of Western Civilization — from Dante to Dostoevsky — together. Inside, you’ll get:

Live community book discussions (bi-weekly)

New, deep-dive literature essays every week

The entire archive of book reviews + our 100 great texts reading list

Our first discussion on Confessions by Saint Augustine is on October 28th at 12pm ET. Bring your thoughts, questions, and favorite passages!

Sign up below to attend — all paid members can join the live discussion up on stage…

Note: paid subscribers via Substack will automatically receive an access link for the live calls.

The Boy from Thagaste

Augustine was born in 354 AD in a North African town called Thagaste. His father, Patricius, was a Roman official who cared about reputation and comfort. His mother, Monica, was a Christian who prayed constantly for her family. Augustine inherited both of them. From his father, he learned ambition. From his mother, he learned longing.

As a boy, he was quick with words and good at winning arguments. He hated school but loved reading. He wanted to impress people. He later said he was good at making lies sound true. That skill made him rich but also proud.

Even as a child, he felt a strange hunger inside him. He wanted to understand why he did the things he did. One day he stole pears from a neighbor’s tree, not because he wanted them, but because it was wrong. That moment stayed with him. It became a symbol for his whole life. He wanted freedom, but he didn’t know what to do with it.

The Thirst for Pleasure

When Augustine grew up, he left home for Carthage to study rhetoric. Carthage was full of noise and life. It had money, parties, and ambition. He fit right in. He had a mistress, and they had a son named Adeodatus. For years he lived for pleasure and success.

Carthage excited him but also exhausted him. He tried everything that promised happiness, but none of it lasted. The joy always faded. Then he read a book by Cicero called Hortensius. It urged people to love wisdom more than wealth or fame. That book hit him deeply. For the first time, he realized he wanted more than pleasure. He wanted meaning. He began to search for truth.

The Manichees

Augustine joined a sect called the Manichees. They claimed to explain the world as a battle between light and darkness. It sounded clever and logical. They promised clarity. He liked that. For almost ten years he followed their ideas.

They told him sin came from matter, not the will. That let him feel smart without feeling guilty. He liked the idea that he wasn’t responsible for his mistakes. But over time, the system started to fall apart. Their leaders couldn’t answer his questions. The more he asked, the more he realized they didn’t know what they were talking about.

He left them behind, but the emptiness stayed. He was tired of shallow answers. He wanted something real, something that explained both the world and himself.

The Wanderer

At twenty-eight, Augustine left Africa and went to Rome. He wanted a bigger stage. Rome was glamorous, but it disappointed him. His students cheated him. His colleagues were corrupt. He was still chasing something that kept running away.

Soon he moved again, this time to Milan. He became a professor of rhetoric. There he met the city’s bishop, Ambrose. Ambrose was calm, wise, and rational. He spoke about Christianity in a way Augustine had never heard before. It wasn’t emotional. It was intelligent and ordered.

Augustine began to listen. He started going to church, not as a believer but as a thinker. Ambrose’s sermons showed him that the Bible had layers of meaning. It wasn’t primitive or childish as he had assumed. It was philosophical and symbolic. Augustine’s mind started to open.

The Battle Within

By now Augustine was famous and respected. He had everything the world could offer, and he was miserable. He wanted to change but couldn’t. He kept his habits because they made him feel safe. His own desires had become chains.

He described that period as living with two wills. One wanted God. The other wanted pleasure. He said he was “held fast, not by iron, but by the obstinacy of his own will.” He prayed, “Give me chastity and continence, but not yet.”

His conversion didn’t come all at once. It built up like a storm. One day, sitting in a garden, he broke down. He cried out, “How long, O Lord? Why not now?” He heard a voice, like a child singing, “Take up and read.” He opened a Bible and read a passage from Romans about turning away from desire and putting on Christ.

That single moment changed him. “In an instant,” he wrote, “the light of confidence flooded my heart, and all the darkness of doubt vanished away.” He decided to follow God completely.

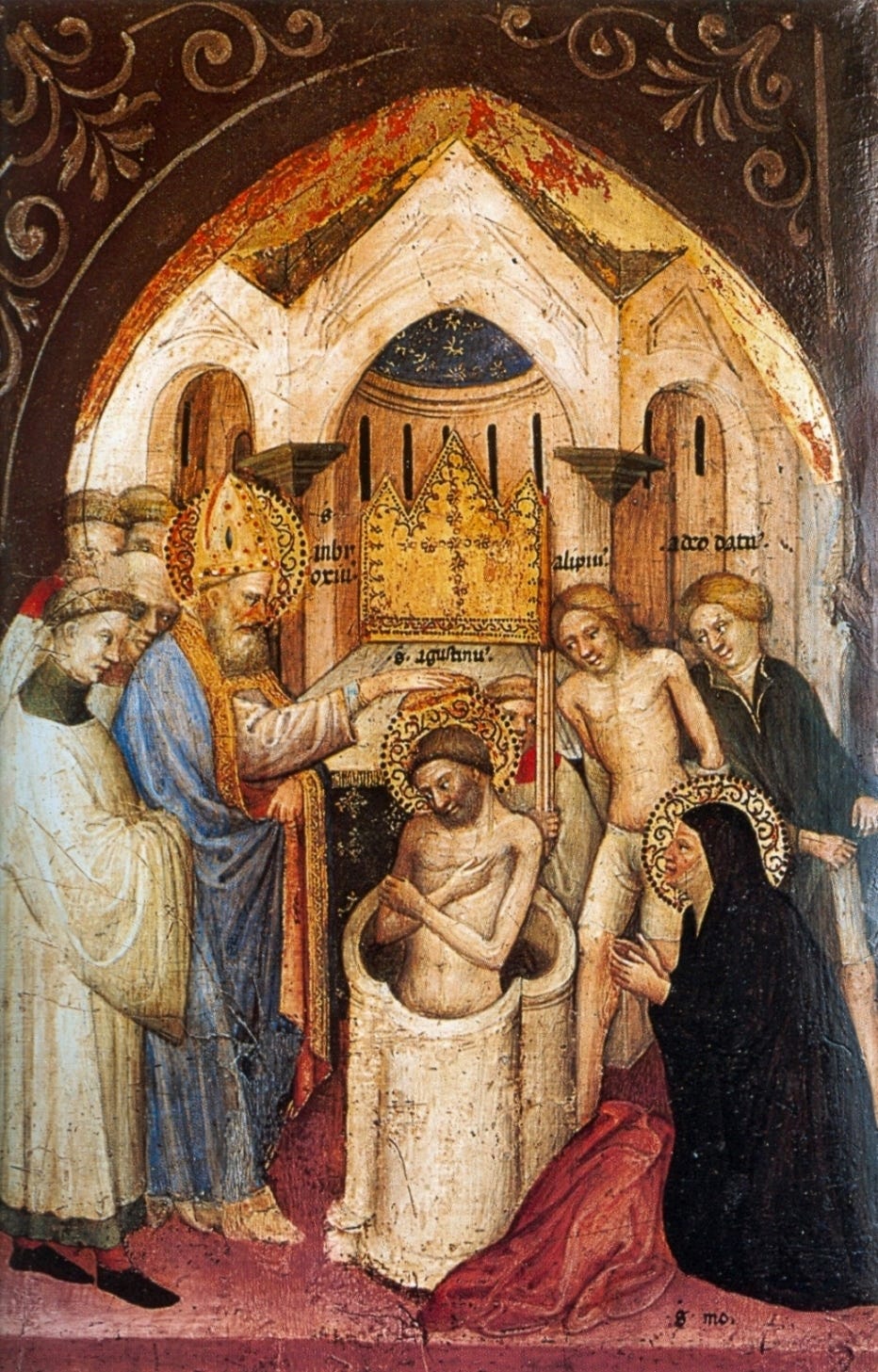

Baptism and Loss

After his conversion, Augustine gave up his career and dedicated himself to faith. In 387, at the age of thirty-two, he was baptized by Ambrose in Milan. His son Adeodatus was baptized beside him. For the first time, Augustine felt peace.

But soon after, both his mother and his son died. His mother Monica passed away in Ostia, the port city near Rome. Before she died, the two had one last conversation while looking out at the sea. They spoke about heaven and eternity. He wrote that for a moment they felt as if they had touched it. She had prayed for him her whole life, and she died happy.

Her death broke him but also freed him. He no longer had anyone to please but God. He returned to Africa with a few close friends and began to live quietly. The man who had once been addicted to noise started to love silence.

The Monk and the Priest

Back in Thagaste, Augustine founded a small monastic community. The group lived simply, prayed, and studied. But Augustine couldn’t stay hidden for long. His wisdom drew people to him.

In 391, during a visit to Hippo, the people pressed him to become a priest. He resisted, but they wouldn’t take no for an answer. Four years later, he was made bishop. For the next thirty-five years, he led the church in Hippo.

He became one of the most powerful voices in Christianity. His sermons were practical and vivid. He spoke in plain language, without show. “Love, and do what you will,” he said. His faith was built on love because he had seen what pride did to him.

The Thinker

As bishop, Augustine wrote more than a hundred books. He tackled theology, philosophy, and history. But two works define him: Confessions and The City of God.

Confessions is his story told directly to God. It’s part memoir, part prayer, part meditation. It reads like a mind turning itself inside out. The City of God is broader. It explains all of history as a struggle between two loves: the love of self and the love of God. The first builds the “City of Man,” full of pride and power. The second builds the “City of God,” full of humility and peace.

When Rome fell in 410, people said Christianity was to blame. Augustine wrote The City of God to answer them. He told them that earthly kingdoms rise and fall, but the real kingdom never ends. Empires collapse, but truth survives.

The Style of His Mind

Augustine’s writing still feels alive because he sounds like someone thinking out loud. He doesn’t lecture. He wrestles. He questions everything, including himself. He’ll start an argument, then stop mid-sentence to pray. He treats faith as discovery, not certainty.

He cared more about honesty than about sounding smart. That’s why he’s so readable. He writes about pride, fear, lust, and grace like someone who knows what they feel like. He doesn’t stand above his past; he looks straight at it.

His reflections on time and memory were centuries ahead of their time. He saw that the mind isn’t just a tool but a mystery. He said the present is always vanishing, the past always remembered, and the future always anticipated. Somehow, all three meet in the soul. That insight still feels new.

The Shepherd and the Soldier

Augustine’s last years were marked by war. The Roman Empire was collapsing, and barbarian armies were everywhere. In North Africa, the Vandals invaded. Hippo was besieged. Augustine stayed with his people.

Even during the siege, he kept preaching and writing. He told people not to lose hope. He was already ill, but he never stopped working. In 430, as the city burned, he lay in bed reading the Psalms. He asked his friends to hang the penitential ones on his walls so he could pray them until the end.

He died at seventy-five. When the Vandals entered the city, they spared his church and his library. The world he was born into had vanished, but his ideas were just beginning to shape the next one.

The Legacy

Augustine’s influence is impossible to measure. He changed theology, philosophy, and even psychology. His reflections on sin, grace, and freedom shaped both Catholic and Protestant thought. His honesty about weakness made faith human again.

He built a bridge between the classical world and the Christian one. He gave the West a new idea of the self… not a public figure, but an inner life known only to God. Every writer who explores consciousness, from Pascal to Dostoevsky to modern psychology, owes something to him.

His story also gave shape to a new kind of hero: the convert. A person who fails, struggles, and then transforms. His life made it possible to see holiness as a journey rather than a state.

The Modern Echo

Reading Augustine today feels strangely familiar. He lived in an age that believed knowledge could solve everything. He saw how that belief left people empty. He lived among ambition, anxiety, and noise. He knew what it was like to be surrounded by ideas but starved for meaning.

He also knew that truth isn’t just discovered by reason. He once tried to think his way into peace and failed. What finally saved him wasn’t logic but love. The mind can recognize truth, but only love can follow it.

That lesson is as relevant now as it was then. The more the world rushes forward, the more Augustine reminds us to look inward. The more people chase attention, the more he reminds us that rest comes from humility. His life is proof that even the most restless heart can find peace when it stops running.

Closing Reflection

Augustine’s life is one long confession. He tells the truth about himself without flinching. He shows how desire, pride, and confusion can all lead back to grace if you’re honest about them. He started out chasing admiration and ended up chasing God.

He wrote, “Late have I loved you, beauty ever ancient, ever new.” Few sentences in literature feel more personal. They carry the sound of a man who finally found what he’d been looking for.

His story ends where every real story of faith ends… not in victory, but in peace. The restless mind finally rests. The seeker finally sees. And the long road home turns out to have been guided all along.

Beautifully written yet giving us the taste of St Augustine's ideas and also the whole person, body and soul. Everything about him leads one to want to know and understand just how one man can be so transformed. Would it could happen to more of us.

Thank you for these passages.