The Last Honest American Writer

A story of work, dignity, and the American soul

John Steinbeck wrote about ordinary people with extraordinary honesty. He was not a theorist or a stylist chasing literary glory. He wrote because he could not ignore what he saw around him. The men and women who filled his stories were not heroes in the usual sense. They were workers, dreamers, and drifters trying to stay alive in a world that did not care much if they succeeded or failed.

He was born in 1902 in Salinas, California, a small town surrounded by fertile valleys and endless fields. Those fields would become the landscape of his fiction. He grew up watching farm laborers move through the seasons, following crops the way sailors follow winds. He saw beauty in their toughness, but also tragedy in their invisibility.

Steinbeck’s writing carried the weight of that contradiction. His stories are about the quiet tension between hope and reality, between what people want and what life gives them. He wrote about America as a place where people live, work, and suffer.

Don’t forget to join our FREE book club!

We started a digital book club to study the great texts of Western Civilization — from Dante to Dostoevsky — together. Inside, you’ll get:

Live community book discussions (bi-weekly)

New, deep-dive literature essays every week

The entire archive of book reviews + our 100 great texts reading list

Our next discussion on Confessions by Saint Augustine is on November 11th at 12pm ET. Bring your thoughts, questions, and favorite passages!

Sign up below to attend — all paid members can join the live discussion up on stage…

Note: paid subscribers via Substack will automatically receive an access link for the live calls.

The Boy from Salinas

Steinbeck’s childhood was unremarkable, which was probably what made it so useful to him. His father worked for the county. His mother was a teacher who filled the house with books. They were not rich, but they were stable. That stability gave him the freedom to observe the world around him.

He loved the Salinas Valley. He called it “the Salad Bowl of the Nation.” It was a place of abundance, but that abundance was built on human exhaustion. Migrant workers came from Mexico, China, and the Dust Bowl states to harvest crops under a burning sun. Steinbeck watched them and wondered how they endured.

As a teenager, he spent summers working on ranches and with field hands. He shoveled manure, drove trucks, and lived in bunkhouses. Those years gave him the vocabulary of labor, the rhythm of how working people talk. His dialogue feels real because it came from conversations he actually had.

He went to Stanford in 1919 and studied intermittently for six years. He read marine biology and medieval literature. He was curious about everything but rarely attended classes. He preferred the company of people who were building or repairing something. When he finally left without a degree, he felt no shame. He already knew he was going to write.

The Apprentice Years

Steinbeck’s early life as a writer was full of failure. He moved to New York in the 1920s hoping to publish stories, but nothing came of it. He worked as a laborer, a caretaker, and even a construction worker. He lived in cheap rooms and sent stories to magazines that never wrote back.

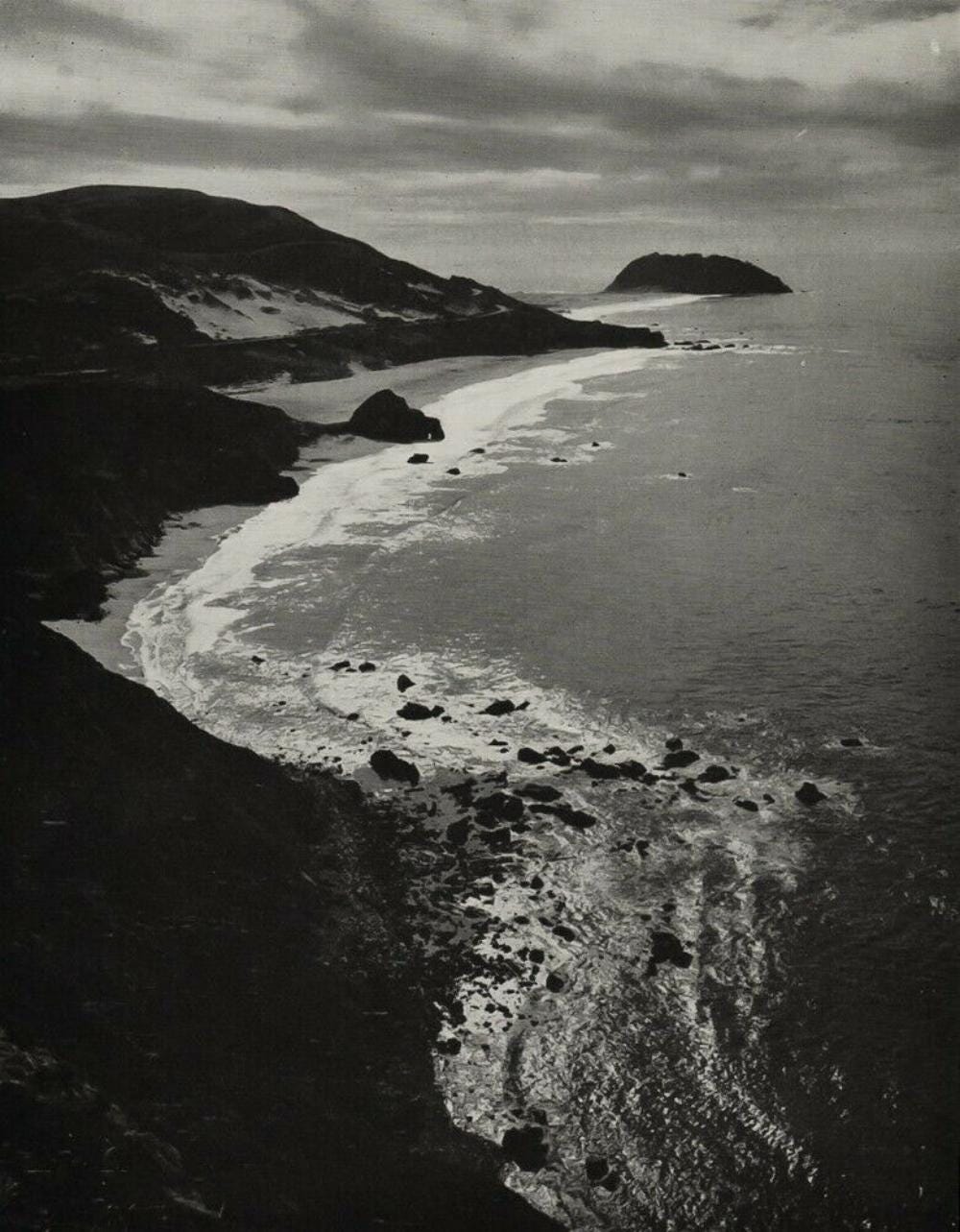

Eventually, he returned to California. The move home changed everything. He lived near Monterey Bay, in a small cottage with little money and few distractions. He spent his days fishing, walking the coast, and writing. Those quiet years taught him patience. He realized that writing was not about talent but endurance.

His first books did not sell. Cup of Gold (1929) was a historical novel about a pirate and went mostly unnoticed. But he kept going. He wrote short novels about California life: The Pastures of Heaven, To a God Unknown, and Tortilla Flat. Slowly, readers began to notice the strange mix in his style… part realism, part myth. He was not just describing people but trying to understand what made them live the way they did.

By the mid-1930s, the Great Depression had swept across America. Steinbeck saw its effects everywhere. Families lost homes and farms. Workers traveled by train looking for jobs that no longer existed. It was a time of collapse, and he decided to write about it.

The Grapes of Wrath

In 1939, Steinbeck published The Grapes of Wrath. It changed his life. The book follows the Joad family, tenant farmers from Oklahoma who lose their land and head west to California. They are chasing work and dignity, but what they find is exploitation. The novel reads like a road story, a tragedy, and a prayer all at once.

Steinbeck did not invent the Dust Bowl migrants. He had met them. He spent weeks in camps listening to their stories. He described the dirt under their nails and the fear in their eyes when police came. He gave them names and voices, which made them real to readers who had never thought about them before.

The book caused outrage among landowners and politicians. California growers accused him of spreading lies. The Associated Farmers of California called him a communist. But ordinary people knew he was telling the truth. The book sold hundreds of thousands of copies and won the Pulitzer Prize.

More important than the prize was what the book represented. It gave the poor a language. Steinbeck showed that the struggles of farmers and workers were not just personal misfortunes but part of a larger story about justice and belonging.

Of Mice and Men

Before The Grapes of Wrath, Steinbeck had already written Of Mice and Men (1937), which remains one of his simplest and most perfect works. It tells the story of two migrant workers, George and Lennie, moving from job to job in California. George is small and sharp. Lennie is big and slow, with the strength of a giant and the mind of a child. Together they dream of owning a small piece of land.

The book is short, but it carries the weight of a whole life. It is about friendship, loneliness, and the fragile nature of dreams. The tragedy comes not from malice but from misunderstanding. Everyone in the book is trying to survive, and survival leaves little room for gentleness.

Steinbeck wrote it like a play, with scenes unfolding in a few settings. The simplicity of the structure hides how profound the story is. He once said that every writer has one thing he must say, and all his books are just attempts to say it better. Of Mice and Men might be that one thing.

The Philosopher of Work

Steinbeck believed that work gave meaning to life. He admired people who built things, who fixed engines or plowed fields or fished for sardines. He thought the world belonged to them because they kept it running.

His book Cannery Row (1945) celebrates that kind of life. It takes place in Monterey among fishermen, drunks, and scientists. The characters are poor but free. They live by improvisation and instinct, not by schedules or ambitions. The book feels lighter than his other works, but underneath the humor is a serious idea: that dignity does not come from wealth or education but from the way you live your days.

He loved science almost as much as literature. His friendship with the marine biologist Ed Ricketts influenced everything he wrote after the 1930s. Ricketts taught him to see the world like a naturalist, to look closely and describe what is actually there. Together they collected marine specimens and talked late into the night about philosophy and ecology. Those conversations shaped The Log from the Sea of Cortez, a travel book disguised as a meditation on life.

For Steinbeck, writing was a form of work no different from fishing or farming. It was his way of paying attention. He did not want to be a moralist. He wanted to observe how people actually behaved, and what they revealed about the human condition when they were tired, hungry, or hopeful.

War and Witness

When World War II broke out, Steinbeck worked as a war correspondent. He traveled with American soldiers in Europe and wrote dispatches for the New York Herald Tribune. The experience changed him. He saw courage, boredom, and fear. He learned that men at war were not heroes or villains but ordinary people trapped in extraordinary circumstances.

He turned those experiences into The Moon Is Down (1942), a novel about a small town under enemy occupation. It is not about victory or defeat, but about resistance… the quiet kind that happens in hearts before it happens on battlefields. The book was banned in some countries but secretly printed by resistance groups who saw in it a mirror of their own struggle.

War deepened Steinbeck’s sense of tragedy. He saw how easily nations could destroy themselves and how fragile civilization really was. After the war, his writing became quieter, more introspective.

East of Eden

In 1952, Steinbeck published East of Eden, the book he said he had been preparing to write his entire life.