The Books That Inspired Tolkien

The medieval roots behind Tolkien’s modern mythology

Most people think of The Lord of the Rings as a work of pure imagination, springing fully formed from Tolkien’s mind. But Tolkien himself would have been the first to deny that. He was not inventing from nothing. He was drawing on a lifetime of reading, on the medieval myths he loved, on the epics he studied as a philologist, and on the Catholic imagination that shaped how he saw the world. His creativity was extraordinary, but it was also rooted in a deep engagement with the past.

To read the books that inspired Tolkien is to see the hidden architecture of Middle-earth. You begin to notice echoes, whether it is a dragon hoarding treasure, a tragic hero brought down by pride, a vision of kingship tested by weakness, or a lament for a world that is fading away. None of these sources explain Tolkien’s genius, which was his alone, but they show where he found the raw material. They also explain why his stories feel so ancient, as if they belong to an older tradition rather than to the modern world of novels.

Here are some of the works that helped shape The Lord of the Rings…

Don’t forget to join our FREE book club!

We started a digital book club to study the great texts of Western Civilization — from Dante to Dostoevsky — together. Inside, you’ll get:

Live community book discussions (bi-weekly)

New, deep-dive literature essays every week

The entire archive of book reviews + our 100 great texts reading list

Our second discussion on Don Quixote will take place on September 2 at 12pm EST!

Sign up below to attend — all paid members can join the live discussion up on stage…

Note: paid subscribers via Substack will automatically receive an access link for the live calls.

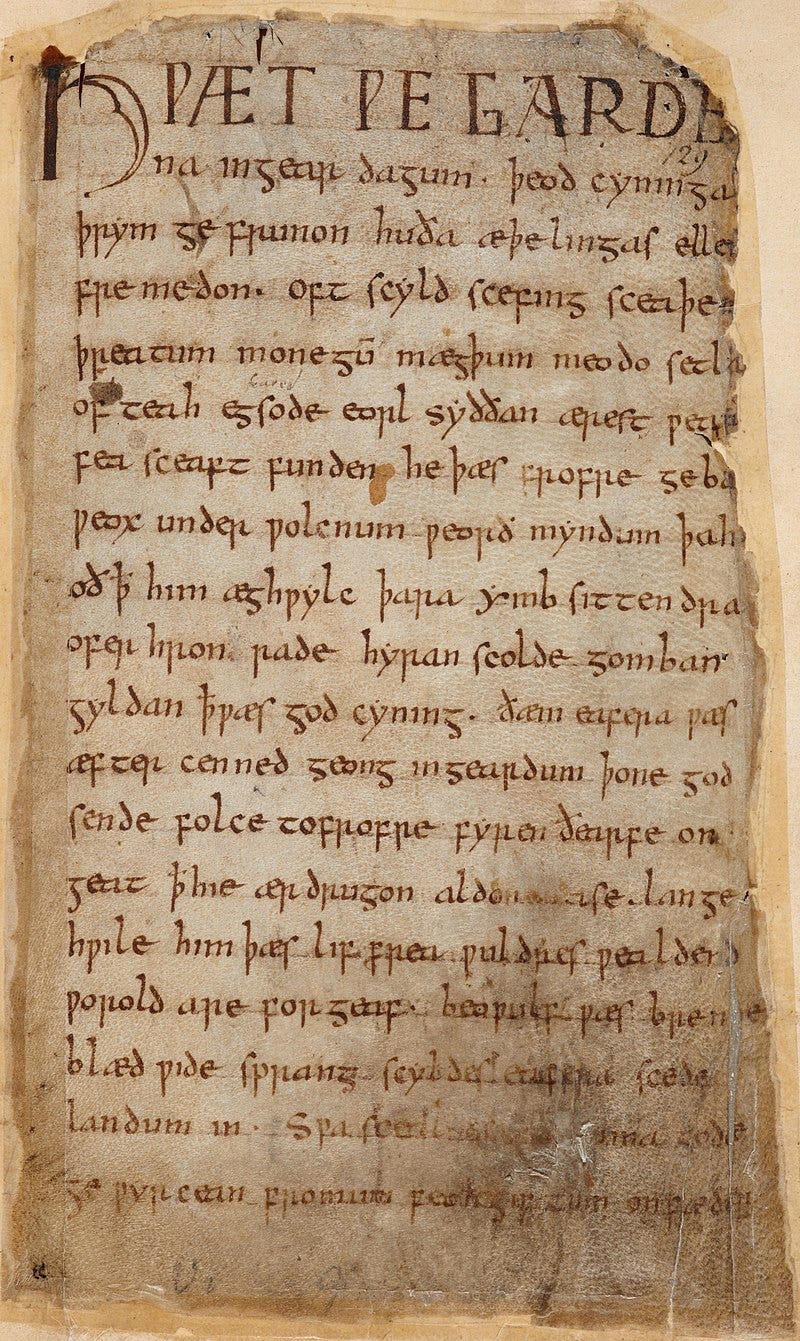

Beowulf

No single poem had more influence on Tolkien than Beowulf. As a philologist, he devoted himself to the study of Old English texts, and Beowulf was the crown jewel of that language. His famous 1936 lecture, Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics, changed the way scholars understood the poem. At a time when most academics treated the monsters as childish leftovers, Tolkien argued that they were the heart of the story, the very element that gave it power.

The traces of Beowulf are everywhere in Middle-earth. The dragon in The Hobbit who sleeps on a mountain of gold is modeled on the dragon of Beowulf. The heroic code of warriors who know they are doomed yet fight anyway echoes in the courage of the Rohirrim as they ride to war. Even the rhythms of the names, the sound of the words, and the cadence of the verses shaped Tolkien’s ear for what an ancient epic should feel like. He did not copy Beowulf. He absorbed it so deeply that it became part of the bones of his own writing, the ground on which he built his world.

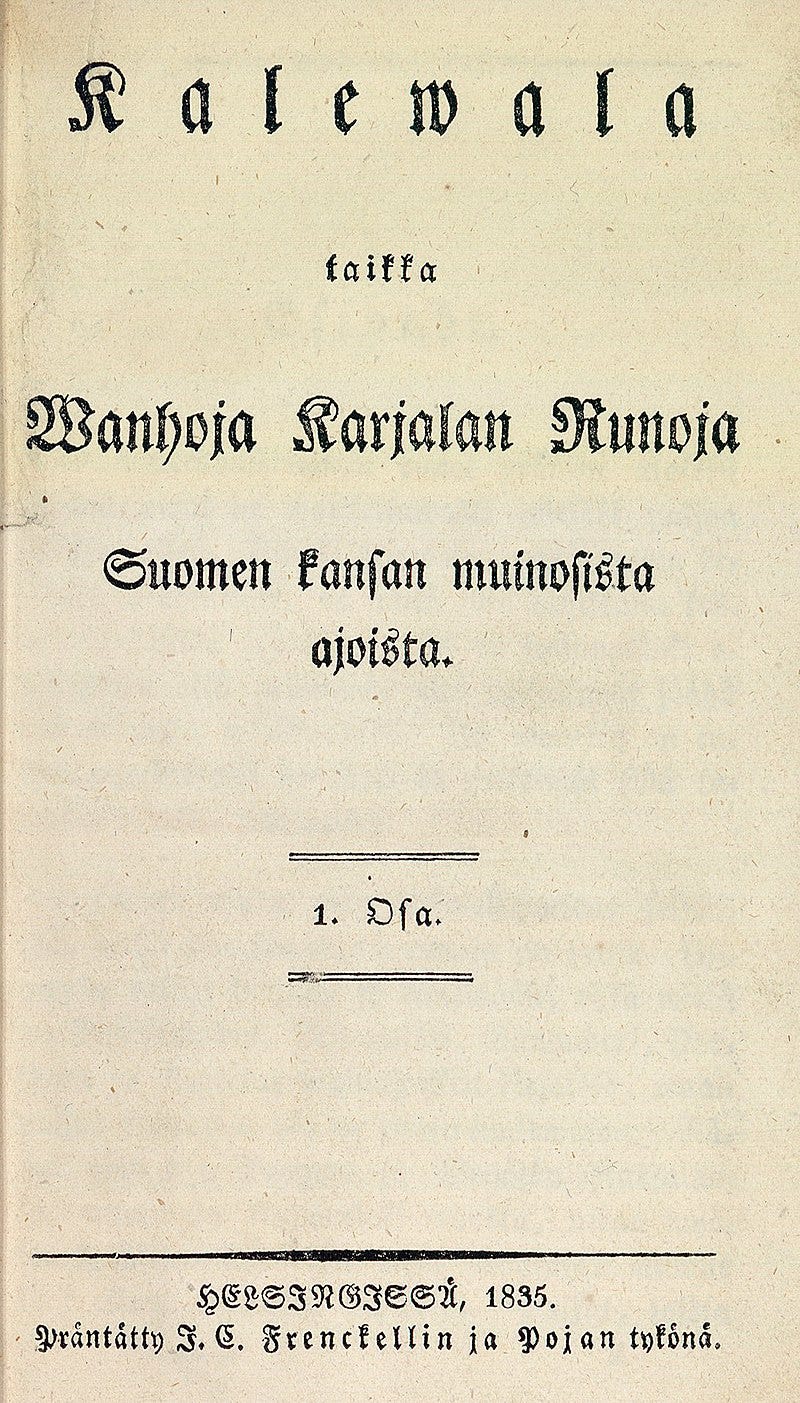

The Kalevala

During his student years, Tolkien discovered the Kalevala, a collection of Finnish myths compiled by Elias Lönnrot from oral tradition. He was fascinated by the language, which sounded so strange and musical compared to the Germanic tongues he already knew. He even began teaching himself Finnish simply so he could read it more closely.

The Kalevala gave Tolkien not only themes but a sense of how myth could be stitched together from fragments and songs. Its hero Kullervo, doomed to tragedy and destruction, was one of the models for Túrin Turambar in The Silmarillion. The idea of a national epic, rooted in folk memory and oral poetry, gave Tolkien a framework for his own desire to create what he once called a mythology for England. The Kalevala showed him that a modern writer could breathe new life into ancient tales and give them coherence and beauty without destroying their mystery.

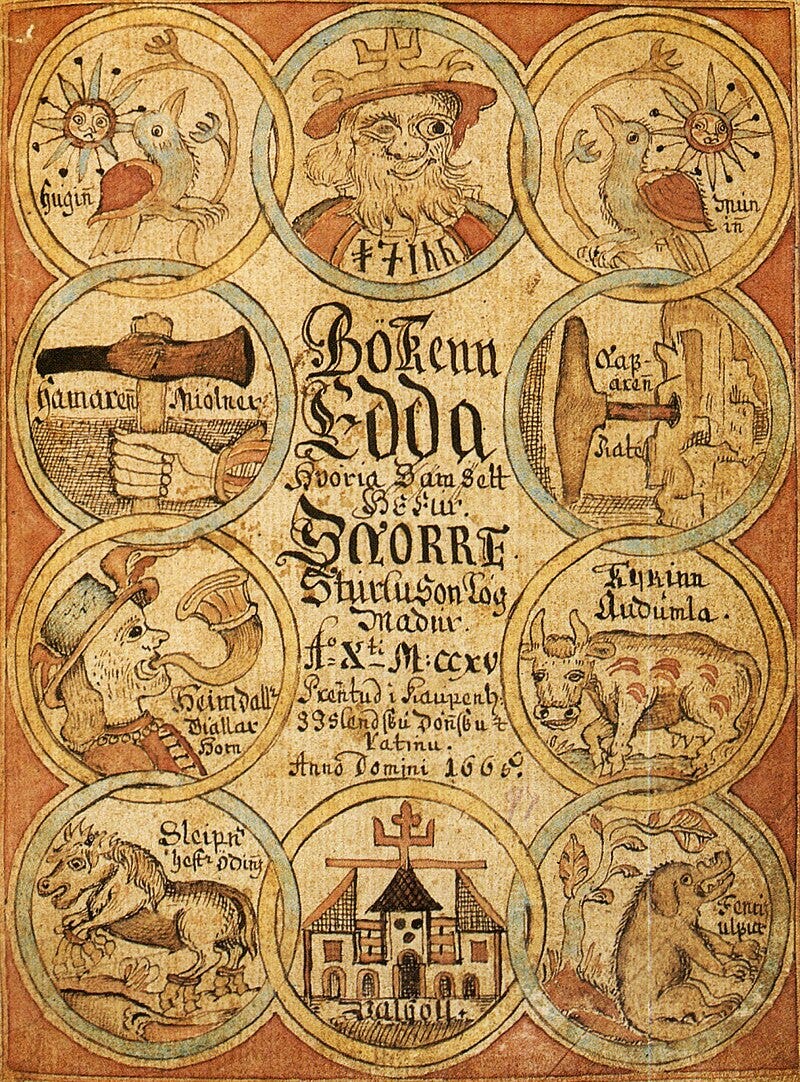

Norse Mythology: The Poetic Edda and The Prose Edda

If Beowulf gave Tolkien the Anglo-Saxon spirit, the Eddas gave him the Norse imagination. These Icelandic texts, written in the Middle Ages but preserving much older material, were filled with gods, giants, dwarves, and the apocalyptic vision of Ragnarök. Tolkien read them in detail and drew inspiration from both their stories and their tone.

The influence is obvious in places. The names of the dwarves in The Hobbit, including Thorin, Fili, Kili, and even Gandalf, come directly from a dwarf catalog in the Völuspá, one of the poems in the Poetic Edda. But the influence runs deeper than names. The Norse vision of a world doomed to destruction, yet still fought for with courage, left its mark on Tolkien. He admired what he called Northern courage, the willingness to fight against overwhelming odds even in the knowledge of defeat. That spirit animates Aragorn as he marches on Mordor, Théoden as he charges the Pelennor Fields, and Boromir as he defends Merry and Pippin. For Tolkien, the Eddas preserved a vision of heroism in a tragic universe, and he carried that vision into his own mythology.

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight

Before Tolkien was a novelist, he was a medievalist, and one of his great loves was Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. He even produced his own translation, which is still admired today, preserving its alliterative verse and musical rhythm. The poem tells the story of a knight of King Arthur’s court who accepts a challenge from a mysterious green warrior, leading to a tale of temptation, honor, and the tension between Christian morality and worldly chivalry.

The influence on Tolkien is subtle but profound. It lies in the way Sir Gawain blends the magical with the moral, treating fantasy not as escapism but as a stage for testing virtue. Frodo’s journey, which tests endurance and humility rather than simple bravery, has something of Gawain’s trial in it. The tension between the fading world of pagan wonder and the dawning light of Christianity, present throughout Sir Gawain, is also central to Middle-earth. Tolkien loved that blending of the supernatural and the sacred, and he carried it with him into his work.

The Volsunga Saga

The Volsunga Saga is one of the great Norse epics, telling the story of Sigurd the dragon-slayer, of cursed treasure, and of tragic love. It was through this saga that the story of a magical ring, the Ring of Andvari, entered European imagination. Wagner would later use it as the basis for his famous Ring Cycle, but Tolkien detested Wagner’s version, which he thought vulgar and distorted. He wanted to reclaim the older myth on its own terms.

The cursed ring in the saga, which brings ruin to all who possess it, is the clearest ancestor of the One Ring. Yet Tolkien gave the idea a new depth. Instead of being only a token of greed or fate, his Ring became a symbol of power, of the temptation to dominate others, of the desire to control rather than serve. In this way he took the raw material of the saga and reshaped it into something with profound moral and spiritual meaning. The Volsunga Saga gave him the skeleton, but he clothed it in his own vision.

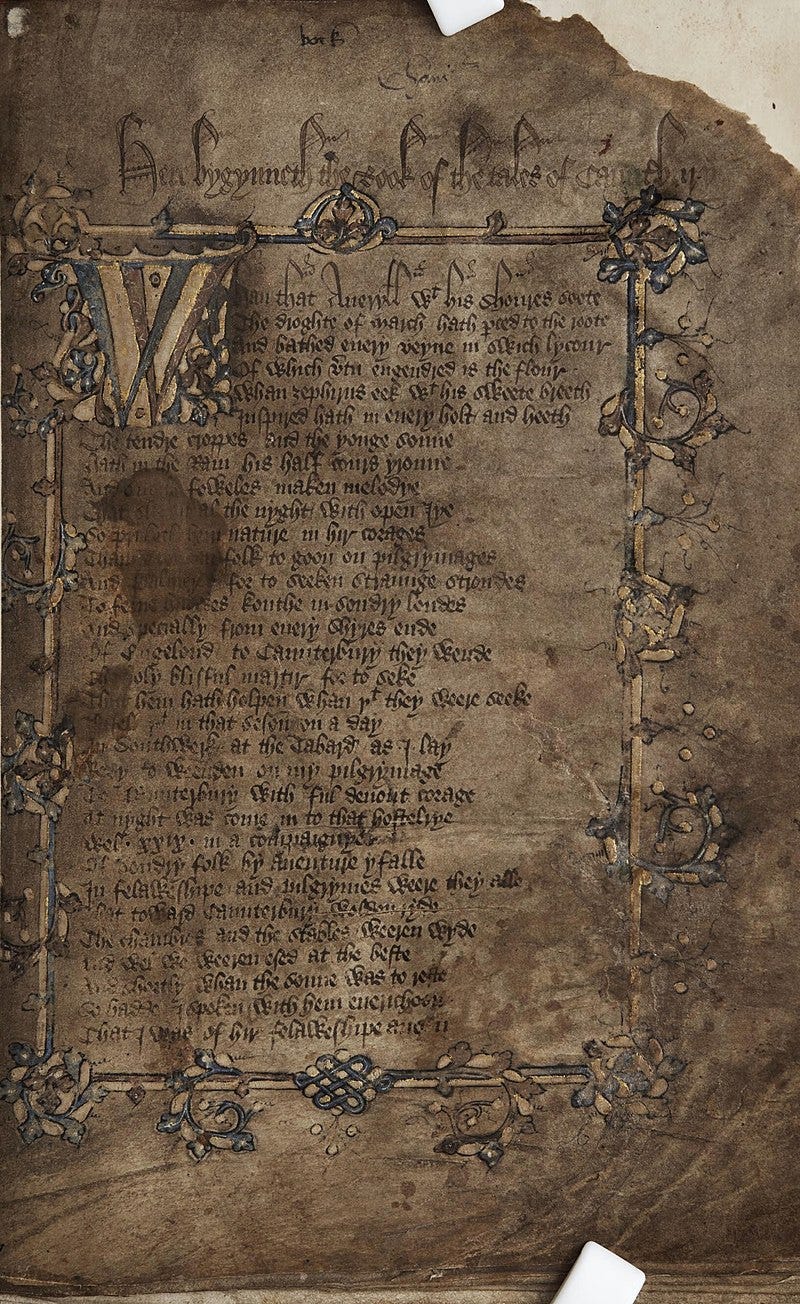

Geoffrey Chaucer, The Canterbury Tales

Tolkien admired Chaucer not only as a poet but as a craftsman of language. The Canterbury Tales showed him how English could be at once musical and earthy, lofty and comic, capable of carrying many voices. Chaucer created a single story that contained pilgrims from every walk of life, each with their own way of speaking and seeing the world.

This polyphonic quality influenced Tolkien’s own storytelling. Middle-earth feels alive because it is filled with distinct voices. The rustic humor of Sam Gamgee, the noble cadences of Aragorn, the elevated speech of the Elves, and the bluntness of Dwarves all come together without losing their individuality. Tolkien’s ability to give each people its own linguistic flavor owes much to the example he found in Chaucer.

The Bible

Finally, it is impossible to understand Tolkien without recognizing the influence of Scripture. He was a devout Catholic, and although he resisted allegory, his imagination was steeped in the rhythms and themes of the Bible. The struggle between light and darkness, the temptation of power, the long unfolding of providence, and the hope of redemption are all Biblical themes refracted through his myth.

The echoes are everywhere if you look for them. Gandalf’s death and return has a Christlike shape. Frodo carrying the Ring up Mount Doom recalls the burden of the Cross. Aragorn’s return as king suggests the messianic fulfillment of prophecy. Tolkien never forced these parallels, but they came naturally from a mind formed by Scripture. His work has the depth it does because it is not just myth but myth seen through the lens of Christian revelation…

Shakespeare's MacBeth had a villain who was prophesied "not to be killed by a man born of a mother." He was killed but by a guy who was born from C-section. The missed opportunity disappointed Tolkien so much, it lead to the creation of Eowyn.

The ents come from there too. A forest had seemingly appeared overnight, but it was only soldiers hiding behind branches.

Nibelungenlied? In Middle High German?

He mentions it in letters and essays.

It depicts a treasure hoard, a magic object which makes the hero invisible (tarnkappe, a hooded cape, not a ring), who slays a dragon, it depicts a dwarf and giants.