Orwell’s 6 Rules of Writing

Why clarity matters more than style

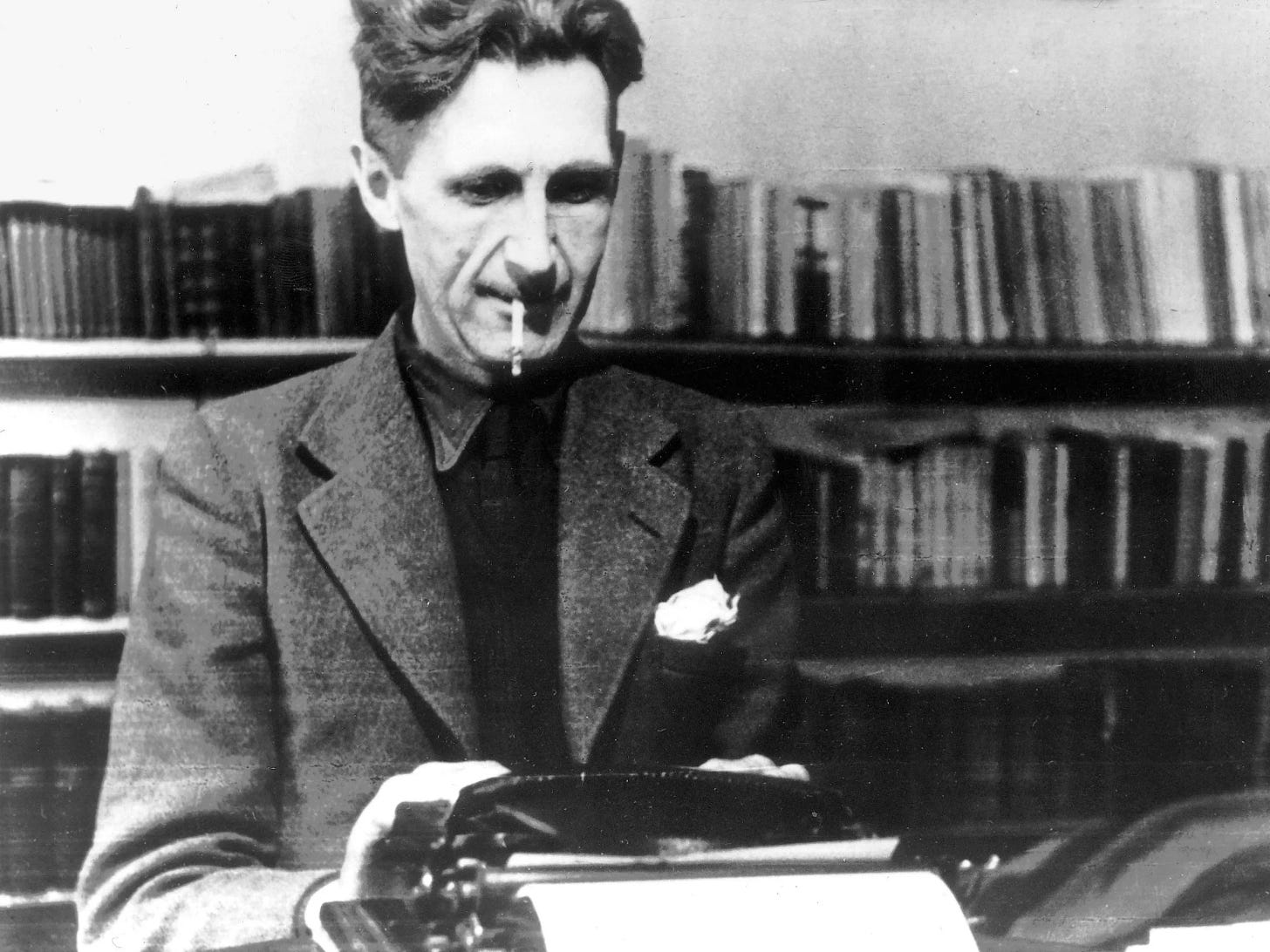

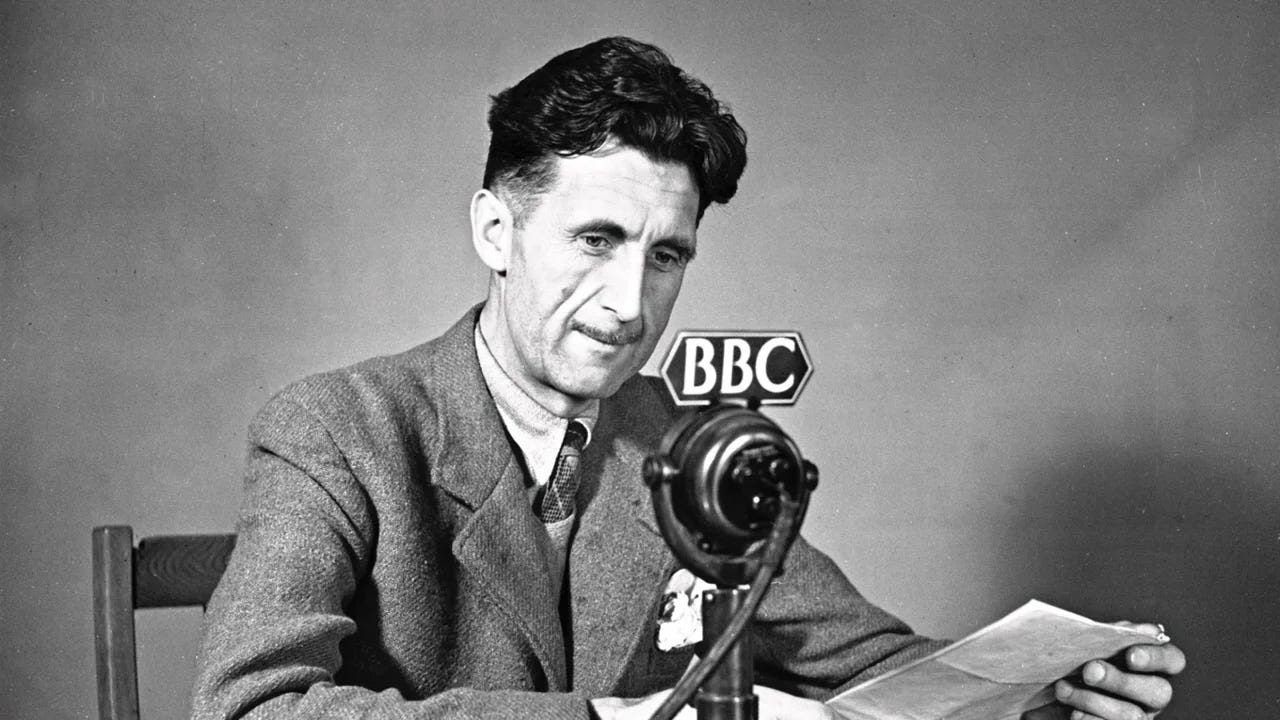

George Orwell cared more about clarity than beauty.

When he wrote about politics, he saw how language was used to manipulate. When he wrote about writing itself, he saw how words could be used to reveal or to hide.

In his 1946 essay Politics and the English Language, Orwell laid down six rules for writing. They are short, almost blunt, but they have outlived most style guides because they are true. If you want to know why some writing feels alive and other writing feels dead, the difference is usually whether the writer followed Orwell’s rules.

These rules were not meant for poets or novelists alone. They were for anyone who wanted to say something and be understood. Orwell believed the corruption of language was tied to the corruption of thought. If people wrote badly, it was usually because they thought badly. If they learned to write clearly, they could learn to think clearly.

That is why his rules are more than writing tips. They are a way of defending the mind against confusion…

Don’t forget to join our FREE book club!

We started a digital book club to study the great texts of Western Civilization — from Dante to Dostoevsky — together. Inside, you’ll get:

Live community book discussions (bi-weekly)

New, deep-dive literature essays every week

The entire archive of book reviews + our 100 great texts reading list

Our second discussion on Don Quixote will take place on September 2 at 12pm ET!

Sign up below to attend — all paid members can join the live discussion up on stage…

Note: paid subscribers via Substack will automatically receive an access link for the live calls.

Rule 1: Never use a metaphor, simile, or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print

When Orwell says this, he is not saying never use metaphors. He is saying never use dead metaphors. Language becomes dead when it is repeated without thought. A phrase like “toe the line” or “the acid test” was once vivid, but after a thousand uses it becomes invisible. Writers reach for these clichés because they are easy. But easy words make lazy readers.

Orwell wanted writers to make language alive again. If you say “time is money,” no one feels anything. If you describe how waiting in a queue feels like watching coins drain from your pocket, people pay attention. The difference is that the first is a cliché, the second is an image born from experience.

Writers often defend clichés because they think readers need familiarity. Orwell thought the opposite. Familiar phrases lull readers into not paying attention. Fresh language wakes them up. When Shakespeare compared Juliet to the sun, the image was new. When modern writers say the same thing, it is an echo. If you want readers to feel, you must make them see, and they only see if the image is your own.

Rule 2: Never use a long word where a short one will do

This sounds obvious, yet almost no one does it. The temptation to use long words is strong because long words feel impressive. Politicians do this most often. They say “utilize” instead of “use,” or “ameliorate” instead of “improve.” The goal is to sound serious, but the effect is the opposite. Readers suspect you are hiding behind the word.

Orwell believed that short words are honest words. “Use” is better than “utilize.” “Help” is better than “facilitate.” A child understands them. A reader trusts them. Good writing does not need to dress itself up. It does not need ornaments. A short word is a small clear window. A long word is a stained glass panel that blocks the light.

Writers often object that some ideas require big words. That is true for technical writing. A physicist cannot avoid “quantum” or “relativity.” But in most cases the long word is chosen for effect, not necessity. It is chosen to look clever, not to be clear. Orwell’s rule is a reminder that you are not here to show off, you are here to be understood.

Rule 3: If it is possible to cut a word out, always cut it out

This may be the hardest rule to follow because writers fall in love with their own sentences. Cutting words feels like killing them. Yet almost every sentence is improved when it is made shorter. A page that once took a minute to read can often be read in forty seconds without losing anything. The reader feels the difference.

Orwell understood that extra words are not harmless. They create fog. A writer who says “it is clear that” or “the fact that” is wasting the reader’s time. The words do not add meaning. They pad it.

Good writers are brutal cutters. Hemingway stripped his prose to the bone. His sentences are lean because he cut without mercy. Orwell did the same. If you compare early drafts of his essays with the final versions, you see whole phrases removed. The effect is energy. Words that remain have power because nothing else is in the way.

The test is simple: read your sentence aloud. If a word adds nothing, cut it. If the meaning survives, the word was never needed. Writers fear cutting because they confuse length with importance. Orwell’s rule reminds us that importance comes from clarity, not from how many words you can put on the page.

Rule 4: Never use the passive where you can use the active

The passive voice hides responsibility. When a writer says “mistakes were made,” the subject disappears. Who made them? No one is sure. The passive voice creates distance. It makes events sound inevitable. The active voice names the actor. “The minister lied.” “The company cheated.” These are sentences with teeth.

Orwell saw how politicians used the passive voice to disguise guilt. A law is “enacted.” A city is “pacified.” Enemies are “eliminated.” The verbs hide the subject. The state becomes a machine that acts on its own. The reader is left with no one to blame.

In ordinary writing, the passive voice makes prose weak. “The ball was thrown by John” is longer and less direct than “John threw the ball.” The difference seems small, but over a whole page it changes the tone. Active sentences are alive. Passive ones are limp.

The rule does not mean never use the passive. Sometimes the actor is unimportant. “The house was built in 1900” does not need a subject. But in most cases, the passive voice is a trick to avoid clarity. Orwell wanted writers to resist it. He wanted words that name names.

Rule 5: Never use a foreign phrase, a scientific word, or a jargon word if you can think of an everyday English equivalent

This rule is often ignored in universities. Academic writing is famous for jargon. Scholars prefer “problematize” to “question,” or “hegemonic discourse” to “common belief.” The effect is to make ideas seem more complicated than they are. Orwell despised this. He saw jargon as camouflage. Writers who use it often do not know what they mean.

Foreign phrases are another form of showing off. Writers sprinkle in Latin or French to give their prose authority. But the reader only feels excluded. Orwell believed that the best writing should include the reader, not shut them out.

The same is true for scientific words. In science they are unavoidable. But outside science they are often used to impress. A writer says “existential” instead of “real,” or “cognitive” instead of “mental.” These words create distance. Everyday English brings ideas closer.

This rule is not about dumbing down. It is about precision. Short, common words are often the most exact. When a reader understands at once, the idea is stronger. When the reader has to pause and decode, the idea weakens. Orwell wanted writing that did not need translation.

Rule 6: Break any of these rules sooner than say anything outright barbarous

This last rule is the safety valve. Orwell knew that rules can become their own kind of cliché. If you follow them blindly, your writing may become mechanical. Sometimes a cliché is the only phrase that works. Sometimes a long word is the only precise one. Sometimes the passive voice is the clearest way to say something.

What matters is not the rule but the purpose. The goal is clarity. The rules are tools to help you get there. But the rule that matters most is honesty. If breaking a rule makes you more clear, break it.

This last rule is the one that separates Orwell from pedants. He did not want writing bound by formulas. He wanted it freed from bad habits. His rules were guides, not chains. Writers who remember that will write with both clarity and freedom.

Why Orwell’s Rules Still Matter

The strange thing about Orwell’s rules is that they have not aged. They were written in 1946, in response to the political jargon of his day, but they could be written today about corporate press releases, academic journals, or government reports. The disease of language he described is permanent. People use words to hide. They always will.

The rules still matter because they remind us that writing is not decoration. It is an attempt to tell the truth. If you fail, the reader feels it. The words may look polished, but they do not connect. If you succeed, the words disappear and the meaning comes through. That is the test.

What Orwell saw clearly is that clarity is rare because honesty is rare. Writers avoid short words because they fear sounding simple. They avoid active voice because they fear naming responsibility. They avoid cutting because they fear losing status. In every case, the problem is pride. Orwell’s rules are a cure for pride. They force the writer to serve the reader, not themselves.

Conclusion

Orwell’s six rules are not magic. They will not turn a bad idea into a good one. But they will protect you from the most common traps. They will stop you from writing what you do not mean. They will force you to see when you are bluffing. That is why they matter.

When Orwell wrote them, he was worried about politics. He thought unclear writing made it easier to accept lies. If words were vague, people would accept anything. If words were sharp, they would resist. His rules were a defense against tyranny as much as against bad prose.

Every generation faces the same choice. We can let our language decay into jargon, cliché, and euphemism, or we can fight to keep it alive. Orwell gave us six rules for the fight. They are simple. They are hard to follow. And they are still the best advice anyone has ever given about how to write.

Love this list! To me it’s also saying “less is more”. You don’t need to do overdo the use of language to get the point across. Keep it simple as long as you know how to craft a theme/argument

Fully agree, I hope my writing achieves this, but it's something I have to practice