How to Write Like Tolkien

If you want to write like Tolkien you first have to understand what made him different from other writers. Most imitations of Tolkien fail because they copy only the surface. They copy the names, the old words, the maps, the invented languages. Those are the decorations. They matter, but they are not the core. What sets Tolkien apart is that his writing feels alive. Middle Earth does not feel like something he made up on a rainy weekend. It feels like something that has always been there and that we are only visiting for a short time.

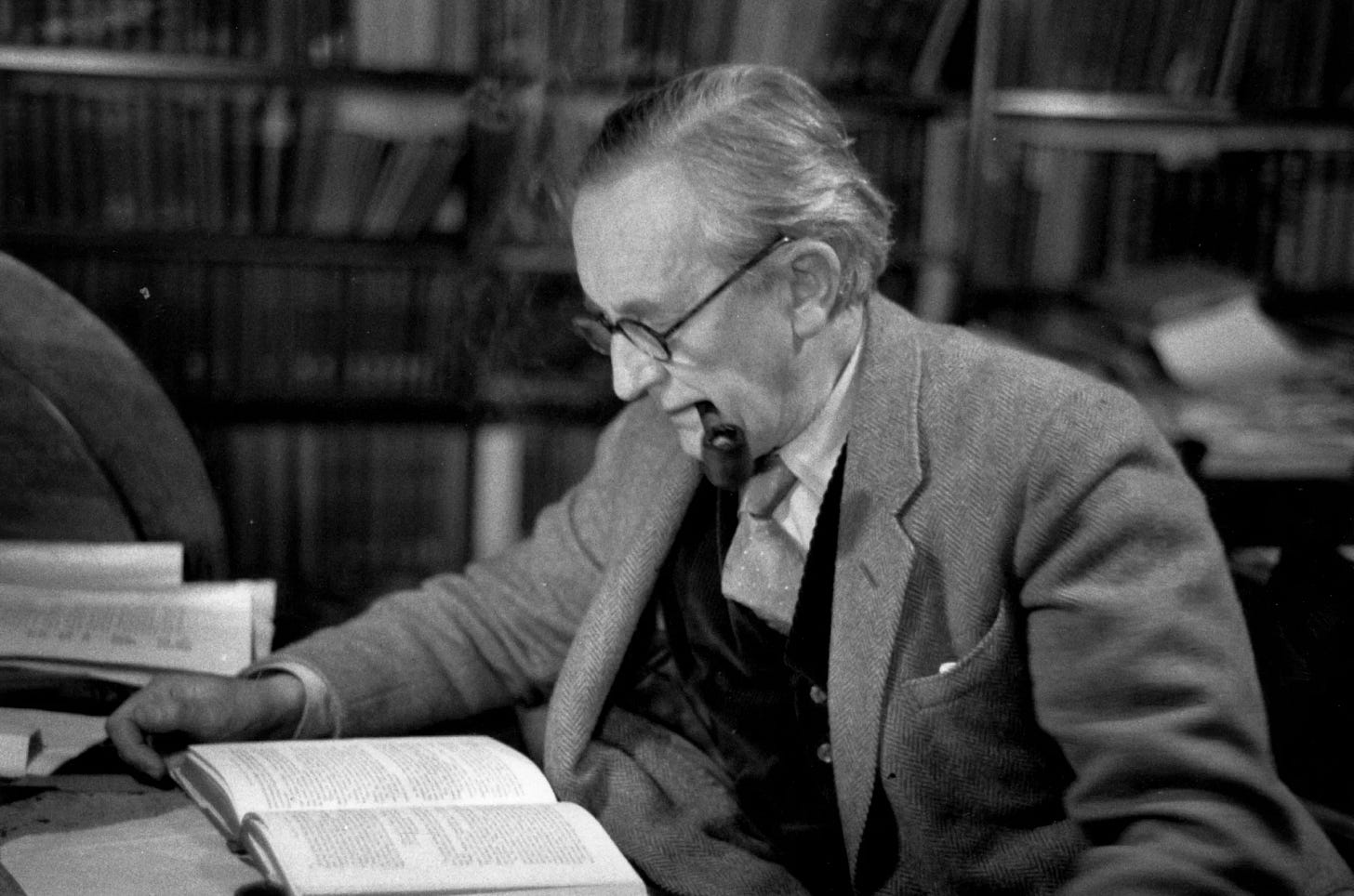

Tolkien never set out to write “fantasy” as a genre. In fact, the category hardly existed when he started. He was a scholar of languages who loved myths. He spent decades writing little poems and stories about elves and dwarves long before anyone thought they would become famous. He wrote them as a private joy. He once called it his “sub-creation,” meaning his way of echoing the creativity of God. That is why his work feels so genuine. He was never aiming at a market. He was trying to delight himself.

This is the first lesson if you want to write like Tolkien. You have to write from love. Not the kind of love where you tell yourself it will sell. The kind where you would do it even if no one ever read it. Readers can feel the difference. When you read Tolkien you sense the deep pleasure he had in making it. If you want your writing to last, you have to approach it with the same attitude.

Don’t forget to join our FREE book club!

We started a digital book club to study the great texts of Western Civilization — from Dante to Dostoevsky — together. Inside, you’ll get:

Live community book discussions (bi-weekly)

New, deep-dive literature essays every week

The entire archive of book reviews + our 100 great texts reading list

Our first discussion on The Count of Monte Cristo takes place on September 16 at 12pm ET!

Sign up below to attend — all paid members can join the live discussion up on stage…

Note: paid subscribers via Substack will automatically receive an access link for the live calls.

Language as the Root

Most people know Tolkien invented Elvish. Fewer realize that his stories were born from those languages. He did not create languages as a decoration. He loved words so much that he invented them for their own sake. He described the joy of making languages as aesthetic rather than utilitarian. For him, a language was like a landscape. Some sounded sharp and rocky, others soft and flowing.

From there, the logic followed. If this is a language, then someone must speak it. Who are they? What kind of culture produces this sound? What are their stories? That is how Middle Earth grew. The world was not designed top down. It sprouted organically from the soil of language.

Even if you never make a language, the lesson holds. Words carry history. A name should feel like something that grew out of a culture. Place names, family names, old songs, they all hint at lives lived before the story begins. That hint of depth is what makes a fictional world feel like a real one.

History Under the Surface

When you read The Lord of the Rings, one of the strongest impressions is that the world has been around for a very long time. You pass through ruins of kingdoms no one remembers. Characters sing about events from centuries ago. The main story feels like a single thread in a tapestry much larger than itself.

That impression was not an accident. Tolkien spent decades writing myths and histories of earlier ages. He wrote far more than he ever published. He was building a world with layers. When you see a ruined tower in the distance, you feel as if Tolkien knows exactly who built it and why, even if he never tells you.

It is that unused depth that gives the books their gravity. A world without history feels thin, like cardboard scenery. A world with history feels alive, because every place suggests something beneath it.

The Sense of Loss

At the heart of Tolkien’s stories is not triumph but loss. The elves are leaving. The old world is fading. Even the great victories come at a cost that cannot be undone. Frodo saves the Shire, but he cannot live in it anymore. He is too wounded.

Tolkien once wrote that his work was about death. That is what gives it emotional weight. The joy in his books is always tinged with sadness. This combination is what he called eucatastrophe, the sudden turn toward joy that does not erase tragedy but shines through it.

That pattern mirrors real life more than a neat happy ending does. Things pass away. Victories cost something. Wounds do not always heal. That is why the stories stay with you long after the last page.

A Moral Imagination

Tolkien disliked allegory, but his Catholic faith soaked through everything he wrote. He saw the world as a struggle between light and darkness, but one in which the small and humble matter more than the powerful. The fate of Middle Earth turns on pity and mercy, not strength.

Think of Frodo sparing Gollum. Think of Gandalf insisting that even the smallest person can change the course of the future. These are not just plot twists. They are expressions of a moral vision. Pride leads to ruin. Power corrupts. Sacrifice redeems.

The point is not to copy his religion. The point is that stories have more force when they come out of convictions about the world. Tolkien’s work feels solid because it was rooted in what he believed was true.

Nature Alive

One reason the Shire feels like home is that Tolkien poured his love of the English countryside into it. He grew up near Birmingham, watching green fields give way to factories. He never forgot the loss. Mordor is not just an imaginary wasteland. It is an industrial landscape stripped of life.

He treated nature not as a backdrop but as a character. Forests have moods. Mountains seem alive. Stars carry hope. Sometimes they literally are characters, like the Ents, but even when they are not, they are never just scenery.

That sense of nature as alive comes directly from affection. He loved trees. He once said he wanted to be remembered as a lover of them. That love shows. If you want your own landscapes to feel real, you have to put that kind of attention into them.

A Patient Rhythm

Tolkien’s books are slow. He spends pages describing landscapes, histories, and songs. Modern readers sometimes complain, but the slowness is part of the spell. The books are not rushing to get somewhere. They are lingering.

That lingering is what lets the world feel full. If you cut all the descriptions, you would have a faster story, but it would feel thin. The long stretches of travel, the songs sung by the fire, the side stories about forgotten kings, all of them build the sense that the world is more than just the plot.

It takes patience to write this way. You cannot be afraid of digression. You cannot be afraid that readers will get bored. The richness comes from taking your time.

Small Heroes

The boldest choice Tolkien made was to put hobbits at the center of the story. They are not warriors or kings. They are ordinary folk who like gardening and food. They would rather stay home. And yet the fate of the world rests on them.

That choice carries two advantages. It makes the story more relatable, because readers can see themselves in hobbits. And it expresses a theme that runs through everything Tolkien wrote: greatness comes from humility.

The smallest person can change the course of history. That is not just a line from the movies. It is the beating heart of his world.

Light in the Darkness

Tolkien had a gift for balancing despair with hope. The darkest parts of the story are never without light. Even in Mordor, Frodo and Sam see a star shining through the clouds. Even in the mines of Moria, Gimli recalls the old glories of his people. Small joys punctuate the struggle, a meal, a song, a moment of laughter.

That balance is crucial. A world of only darkness would be unbearable. A world of only light would feel trivial. Holding both together makes the story feel real. Life is both hard and beautiful, and Tolkien caught both truths at once.

Layers Over Time

The reason Middle Earth feels so thick is that Tolkien spent decades layering it. He wrote poems, myths, languages, and histories long before he wrote the novels. He kept rewriting them. The Lord of the Rings grew out of a mountain of fragments.

That way of working is slower than planning everything in advance, but it produces depth that cannot be faked. Each new piece adds another layer, even if most of it never makes it into the final story. What the reader feels is the accumulation of years of attention.

The Core

When you step back, what made Tolkien’s work different is not just brilliance but devotion. He loved his world into existence. He built it out of languages because he loved languages. He filled it with history because he loved myths. He wrote it slowly because he cared about the details. He poured his convictions into it because they were part of him.

That is the real secret. Not copying the surface, but carrying the same seriousness and love for what you make. If you can find something you love that much, and give it that much patience, your work will have the same quality. Not the same shape, because your loves will be different, but the same life.

There’s no substitute for authenticity.

My wife Jamie has been reading and studying Tolkien for decades; in fact, I've heard her use every point in this article in conversation about his writing (Eucatastrophe is one of her favorite concepts.) She also talks about how literature and story can influence culture. Here's a recent article she wrote contrasting Éowyn vs. modern feminism. This is a political piece, so some may want to avoid it.

https://pjmedia.com/jamie-wilson/2025/08/27/the-poisoned-words-women-believe-tolkiens-eowyn-shows-why-modern-empowerment-feels-like-despair-n4943098

If the moderator feels the article is inappropriate for this forum I'll not be offended if it is deleted; I'm just very proud of Jamie's work and like to share it wherever I can and this is her latest writing on Mr. Tolkien.