How Evil Thinks

A study of temptation, irony, and the anatomy of the soul

When The Screwtape Letters was first published in 1942, it shocked readers. A book written as a series of letters from a senior demon to his nephew was not what people expected from a Christian writer. But that was the genius of C. S. Lewis. He understood that sometimes the best way to explain goodness is to let evil talk. By writing from the perspective of the tempter, he exposed the quiet, logical, and almost polite ways that sin works in daily life. The result is one of the strangest and sharpest spiritual books ever written … both darkly humorous and deadly serious.

Lewis once said he did not enjoy writing it. “It was easy to twist one’s mind into the diabolical attitude,” he wrote later, “but it was not fun.” That comment says much about the book’s depth. The Screwtape Letters is not entertainment. It is a moral X-ray of the human condition, written by someone who knew how subtle evil could be.

Don’t forget to join our FREE book club!

We started a digital book club to study the great texts of Western Civilization — from Dante to Dostoevsky — together. Inside, you’ll get:

Live community book discussions (bi-weekly)

New, deep-dive literature essays every week

The entire archive of book reviews + our 100 great texts reading list

We’re back for our final Count of Monte Cristo discussion on October 14th at 12pm ET. Bring your thoughts, questions, and favorite passages!

Sign up below to attend — all paid members can join the live discussion up on stage…

Note: paid subscribers via Substack will automatically receive an access link for the live calls.

The Premise

The book is a collection of thirty-one letters from Screwtape, an experienced demon, to his nephew Wormwood, a junior tempter. Wormwood has been assigned a human “patient” and must guide him toward damnation. Screwtape offers advice on how to do it… how to exploit pride, boredom, doubt, and habit… while warning against letting the man become too self-aware.

The cleverness of the book lies in its inversion. Because the letters come from a demon, everything is flipped. When Screwtape speaks of “the Enemy,” he means God. When he speaks of “Our Father Below,” he means Satan. This reversal forces the reader to think differently. You begin to see your own life from the perspective of temptation. What would your weaknesses look like to a mind that wanted you to fail?

The idea came to Lewis suddenly, during a dull church service in 1940. He said it began as a picture in his mind: a devil lecturing a younger devil on how to corrupt a soul. The form was perfect for his imagination. It combined his love of satire, his understanding of theology, and his insight into psychology.

The Nature of Temptation

What makes The Screwtape Letters brilliant is its realism. Screwtape’s methods are ordinary. He rarely tells Wormwood to inspire dramatic evil. His advice is to nudge, not push. He says the safest road to hell is “the gradual one… the gentle slope, soft underfoot, without sudden turnings, without milestones, without signposts.”

That sentence captures Lewis’s entire understanding of sin. Most people, he believed, do not lose their souls through great crimes but through small compromises. Evil rarely announces itself. It whispers. It invites distraction, comfort, and self-importance. Screwtape advises his nephew to keep the man busy with trivialities… politics, arguments, petty irritations… anything that keeps him from quiet reflection.

Lewis wrote during wartime, when fear and propaganda filled the air. Screwtape tells Wormwood to exploit both patriotism and pacifism, whichever works best. The point is not ideology but distraction. The devil’s goal is not to make a man wicked in any spectacular way, but to make him forget he has a soul.

The Psychology of the Soul

Lewis was not a psychologist in the modern sense, but his understanding of the human mind is remarkable. He saw that temptation works by twisting virtues, not inventing new vices. Courage becomes recklessness. Humility becomes pride in being humble. Love becomes control. Every sin begins as something good that has been bent.

In one letter, Screwtape explains that pride is easiest to cultivate through self-consciousness. If the patient begins to think about his humility, he will soon lose it. Another letter describes how to turn religious feeling into habit and habit into boredom. Wormwood is told to keep the man thinking about “his feelings” rather than about God. The goal is to turn worship into self-analysis.

Lewis understood how easily people mistake emotion for faith. Screwtape knows this too. When the man feels dry or distant from God, Wormwood is told to make him believe the faith has failed. The truth, Lewis suggests, is the opposite. Real faith begins when feelings fade. That is when the will has to act. The devils know that a Christian who perseveres without pleasure is more dangerous to hell than a dozen who live on enthusiasm.

The Banality of Evil

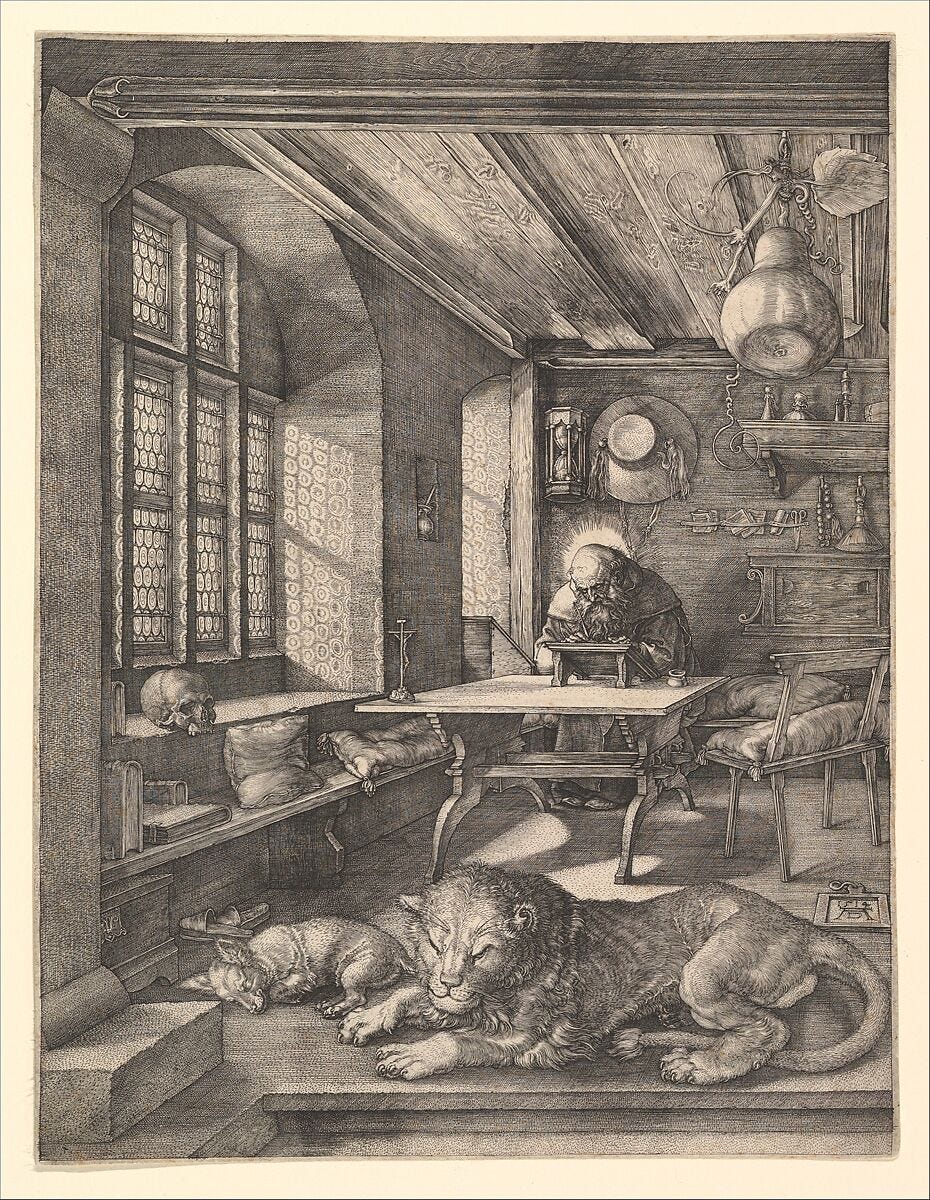

One of the book’s quiet achievements is how unglamorous evil appears. Screwtape is not grand. He is bureaucratic. He worries about reports, promotions, and efficiency. Hell in this book resembles an office. Letters move through channels. Mistakes are punished. Everyone schemes for advancement.

This was Lewis’s way of mocking the modern world’s tendency to make evil dull and organized. Having lived through totalitarian regimes and bureaucratic cruelty, he saw how institutions could depersonalize both sin and suffering. Screwtape’s hell is not fire and chaos; it’s hierarchy and paperwork.

This tone gives the book its humor but also its unease. Screwtape’s intelligence is chilling precisely because it sounds so reasonable. His logic is the logic of a clever cynic who sees morality as a tool and faith as a weakness. Lewis understood that the devil’s most effective disguise is not horror but normality. Evil, in the modern world, looks professional.

The Patient

The human at the center of the book is never named. He could be anyone. We learn only fragments: that he’s an ordinary man, living an ordinary life, dealing with ordinary temptations. That choice was deliberate. Lewis wanted readers to recognize themselves. The letters’ power comes from that mirror effect.

Through Screwtape’s eyes, we watch the man’s inner life unfold. He becomes a Christian early on, which frustrates Wormwood. From that moment, the battle changes. The devils no longer try to stop belief but to corrupt it. They try to make him proud of being religious, or scornful of other believers. They want him to pray for his mother’s faults instead of his own.

Lewis uses this small domestic battlefield to reveal how spiritual life really works. The drama is internal… not spectacular acts of virtue or vice, but small choices made in thought and motive. The man’s salvation depends on awareness. The more clearly he sees himself, the less power the devils have.

The War Within

Every letter reflects the same war… not between people but within the soul. Screwtape calls it “the law of undulation.” Human life, he says, moves in waves of emotion and will. There are highs and lows, times of light and times of dryness. The devils want the man to think his faith depends on these moods. The Enemy (meaning God) uses them to teach him that love is not a feeling.

Lewis understood spiritual fatigue. His own life had been marked by suffering… losing his mother, enduring the trenches, watching friends die. He knew that perseverance in faith is not easy. Through Screwtape’s mockery, he shows that endurance itself is victory.

One of the most moving passages comes when Screwtape laments the moment humans pray during silence. “When he looks around upon a universe from which every trace of Him seems to have vanished, and asks why he has been forsaken, yet still obeys, our cause is in the utmost danger.” That line sums up the essence of Christian courage as Lewis saw it… faith without evidence, obedience without comfort.

The Role of Habit

Lewis believed character is built in daily habits. Each choice nudges the soul closer to heaven or hell. Screwtape’s strategy reflects that view. He tells Wormwood to focus not on big sins but on routines. A distracted prayer, an unkind word, a neglected duty… these are the small stones that pave the road downward.

The devil’s favorite tool is mediocrity. If the man can be made comfortable and busy, he will never ask deep questions. Screwtape says, “You will find that anything or nothing is sufficient to attract his wandering attention.” Lewis saw this long before smartphones or social media, but the insight feels prophetic. The enemy of faith is not atheism but distraction.

He also writes about pleasure in an unexpected way. Screwtape admits that pleasure is dangerous to hell because it comes from God. The devils can only twist it. This shows Lewis’s earthy realism. He didn’t see Christianity as denial of joy, but as the right use of it. Evil can only counterfeit; it cannot create.

The Limits of Hell

As the letters progress, Wormwood’s situation worsens.